Black holes love to eat. Among her favorite delicacies is the interstellar gas. On Thursday, astronomers announced that they had succeeded in making the most detailed observation yet of large clouds of gas close to a supermassive black hole.

Avi Blizovsky

Black holes love to eat. Among her favorite delicacies is the interstellar gas. On Thursday, astronomers announced that they had succeeded in making the most detailed observation yet of large clouds of gas close to a supermassive black hole.

Among other things, the gas carbon monoxide is found in this cloud. The scientists made an effort to observe the last stages of gas consumption, because black holes are far from us and because the eating process creates a lot of light that floods what is happening.

"We have hints that the cold gas clouds are moving toward the center of the galaxy," says Johannes Staguhn, a radio astronomer at NASA and Science Systems and Applications. Meanwhile, the cold gas organized in a ring around the center of the distant galaxy is also a hotbed for the formation of new stars.

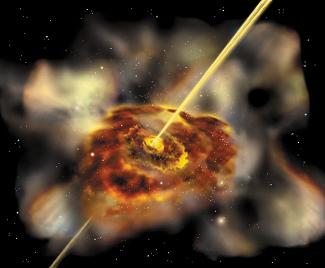

The findings, along with an artist's rendering of the scene as it might appear up close, were published at a meeting of the American Astronomical Union.

Stagon and his colleagues studied an extremely active galaxy, a quasar, located 800 million light-years away from us. The quasars shine brightly. The new observation is a step toward finding a link between star formation and bright quasar activity, likely caused by matter falling into a supermassive central black hole.

It is believed that while some of the gas clouds collapse under their own weight to form stars, parts of them flow towards the black hole. The enormous gravity of the black hole accelerates the gas to the speed of light, heating it and creating tremendous radiation before most of the gas is swallowed by the black hole. The gas clouds surround the center of the quasar at a distance of 4,000 light years. At a speed of 200 kilometers per second they contain over a billion suns worth of material.

The researchers also found evidence that a quasar may interact with neighboring galaxies. Galaxy mergers are the process that fuels star formation, and Stagon wants to learn whether the same is true when quasars merge into other galaxies.

The observations were made by the radio-telescope array of the Berkeley-Illinois-Maryland Association in Hat Creek, California, Berkeley Illinois Maryland Association (BIMA).