The development of the disease in celiac patients is probably related to sensitivity to the protein common in industrialized dairy products. The findings pave the way for early detection of the disease and its prevention

The tooth enamel, or enamel layer, is the white layer that covers and protects the teeth and is considered the hardest tissue in our body and the richest in minerals. When this shell does not develop properly, the teeth become sensitive to heat, cold or acidic foods, and are characterized by a yellowish color and a crumbling appearance. One out of ten people suffers from damage to the development of the tooth enamel, and in most cases the reason for this is unknown. In a new study thatRecently published in the scientific journal Nature, Prof. Jacob Abramson and his group from the Weizmann Institute of Science revealed a new autoimmune disease in children that affects the development of tooth enamel. This disease is common among patients with a rare genetic syndrome but also among children with celiac disease, and is characterized, among other things, by sensitivity to the protein common in industrialized dairy products. The new findings are expected to enable early detection of the disease and even pave the way for its prevention.

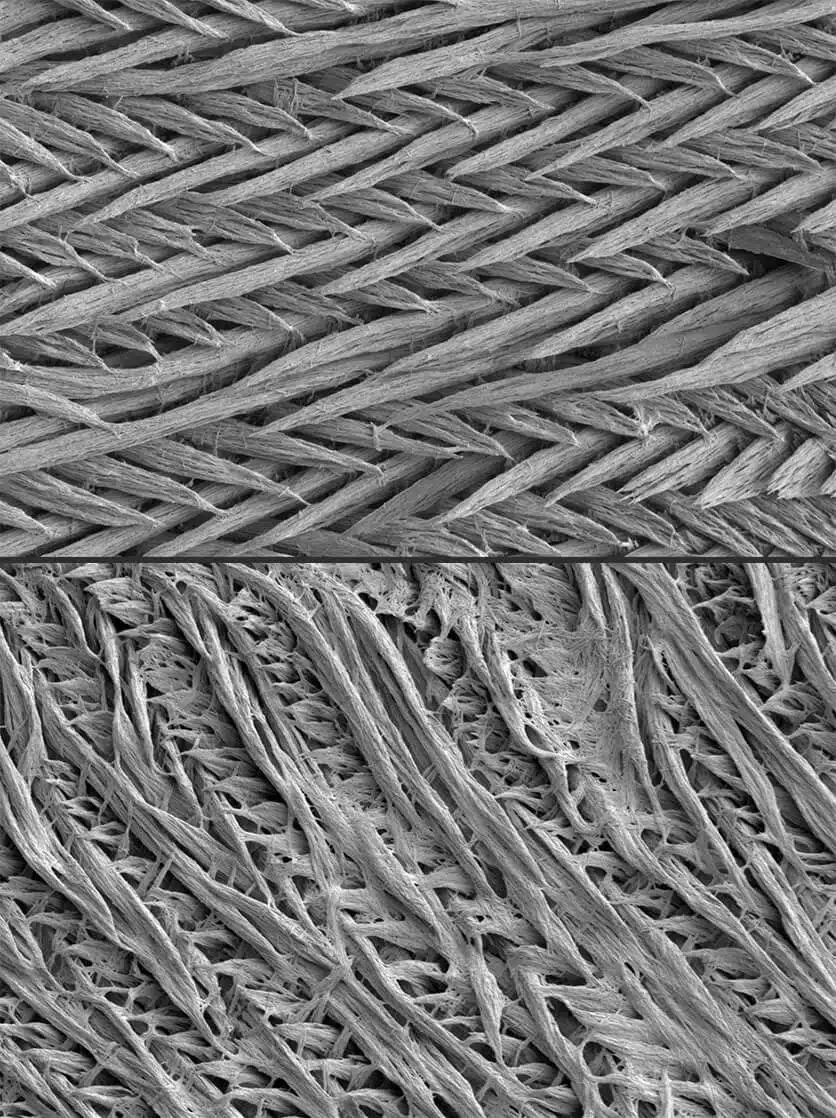

Tooth enamel is mostly made up of mineral crystals that are gradually assembled on top of scaffolding proteins. After the crystals are assembled, the scaffolds break down and a thin but extremely strong layer remains that wraps around our teeth and protects them. Among the majority of patients with a rare genetic syndrome known as APS-1, a strange phenomenon was identified: while the enamel layer of the milk teeth developed in a completely normal manner, precisely in the permanent teeth there was a failure in the enamel development process. Since APS-1 patients suffer from a variety of autoimmune diseases, Prof. Abramson and his group hypothesized that it is possible that the damage to the enamel also originates from an autoimmune syndrome, meaning that it is possible that the immune system itself is the one attacking the developing enamel. An autoimmune disease can occur when T cells or antibodies activate an immune response against the body itself. In order to avoid "the fire of our forces", during the development of T cells in the thymus, they are shown segments of self proteins from different tissues and organs in the body, and this is to educate them not to attack these proteins; At the same time, T cells that fail the task are destroyed and identify self proteins as potential targets.

This education goes awry in patients with APS-1 syndrome as a result of a mutation in a control gene called Aire responsible for expressing all those self-proteins presented to T cells in the thymus. In the new study, a team of scientists from the Institute's Department of Immunology and Biological Regeneration, led by research student Yael Gruper, tried to understand how mutations in Aire lead to a failure in the development of tooth enamel. The researchers revealed that in the absence of Aire, proteins important for enamel development are not presented to T cells in the thymus. As a result, cells that may recognize these proteins as targets are released and stimulate the production of antibodies to the enamel proteins. But why do the autoantibodies cause damage to the permanent teeth and not the baby teeth?

The explanation for this is that the baby teeth development process takes place in the embryonic stage, when the immune system is not yet developed, and therefore there is no production of autoantibodies. On the other hand, the enamel development process of the permanent teeth starts from birth and continues until the age of six, when the immune system is sufficiently developed and able to damage the enamel development. Moreover, the researchers even identified a correlation between high levels of antibodies to enamel proteins and the severity of damage to its development in children with APS-1. This finding strengthens the hypothesis that the presence of autoantibodies in childhood may lead to dental damage.

In an attempt to find out how the known celiac disease due to its damage to the intestine also causes damage to the tooth enamel, the researchers first checked whether celiac patients also have the production of autoantibodies to the enamel proteins. They identified that a significant number of them have autoantibodies, similar to those of the APS-1 patients. However, if the training processes in the thymus of celiac patients are apparently normal, why would they develop these antibodies? The researchers hypothesized that there may be proteins found both in the intestinal environment and in the tooth tissue, and that these proteins are important in the enamel development process. According to this scenario, antibodies that recognize the proteins in the intestine may move through the bloodstream to the tooth tissue, disrupting the enamel formation process there.

Since many celiac patients develop a sensitivity to cow's milk, the researchers focused on the kappa-casein protein, which is a major component of dairy products. They found that the human version of kappa-casein is one of the main components of the scaffolding needed for the formation of the enamel layer and that most children diagnosed with celiac disease have high levels of antibodies to cow-derived kappa-casein. That is, theoretically, the antibodies to the milk protein produced in the intestine, may also act against the human version of this protein in the teeth.

These findings may have implications for the food industry. "Similar to the lesson we learned from gluten, we believe that consuming large amounts of dairy products may lead to the creation of autoantibodies to kappa-casein," explains Prof. Abramson. "This protein increases the yield of cheese that can be produced from the milk, so the dairy industry deliberately increased its concentration in cow's milk. But our research reveals that this protein functions as an autoimmunogen, meaning it may trigger an immune response against the body itself."

Defects in tooth enamel are quite common in the population, not only in celiac and APS-1 patients. "Many people suffer from damage to the development of tooth enamel for an unknown reason," says Prof. Abramson, "it is possible that the new disease we discovered and the possibility of identifying it with a blood or saliva test, will give those people a name for their disease. Also, early diagnosis in children may allow preventive treatment in the future."

Among others, Liad Glanz, Dr. Yonatan Herzig, Dr. Yael Goldfarb, Dr. Yan Dubesh, Dr. Noam Kadori, Osher Ben-Non, Amit Binyamin, Bar Lavia, Tal Givoni, Razi Halaila, Tom Goma and Carmel Agent from the Department of Immunology and Biological Regeneration at the Weizmann Institute; Dr. Shefra Ben-Dor and Dr. Esther Feldmaser from the Department of Life Sciences Research Infrastructures at the Institute; Prof. Esti Davidovich from the Hadassah School of Dentistry and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and Dr. Noa Tal, Prof. Dror Shuval and Prof. Raanan Shamir from the Schneider Pediatric Center in Israel and Tel Aviv University.

More of the topic in Hayadan: