How did the elementary school teachers who immigrated to Israel in the mass immigration of the 50s affect the Israeli education system

The education system in Israel is mainly based on the one established by the settlement from the beginning of the Zionist settlement. After the establishment of the state, the Ministry of Education was established and laws regulating the education system were enacted, including the Compulsory Education Law 1949-1953 and the State Education Law XNUMX-XNUMX.

"Education is a significant social agent that shapes ideological perceptions. It is impossible to understand a society without knowing the factors that shaped it, and the education system is a major factor in this field," says Dr. Tali Tadmor Shimoni, historian of education, head of the Israel State Studies track at Ben Gurion University. "Every educational system strives to shape the image of a desirable graduate. When studying the contents of the study and the transmitters of the messages, the teachers and the administrators, it is possible to understand what kind of person will be shaped in the future, as well as his beliefs and occupations. Today, for example, the subject of agriculture is hardly taught because it lacks the ideological aura that accompanied it in the past. It is not 'economic', so subjects such as mathematics and computers are emphasized. The ceremonies, on the other hand, remained as they are."

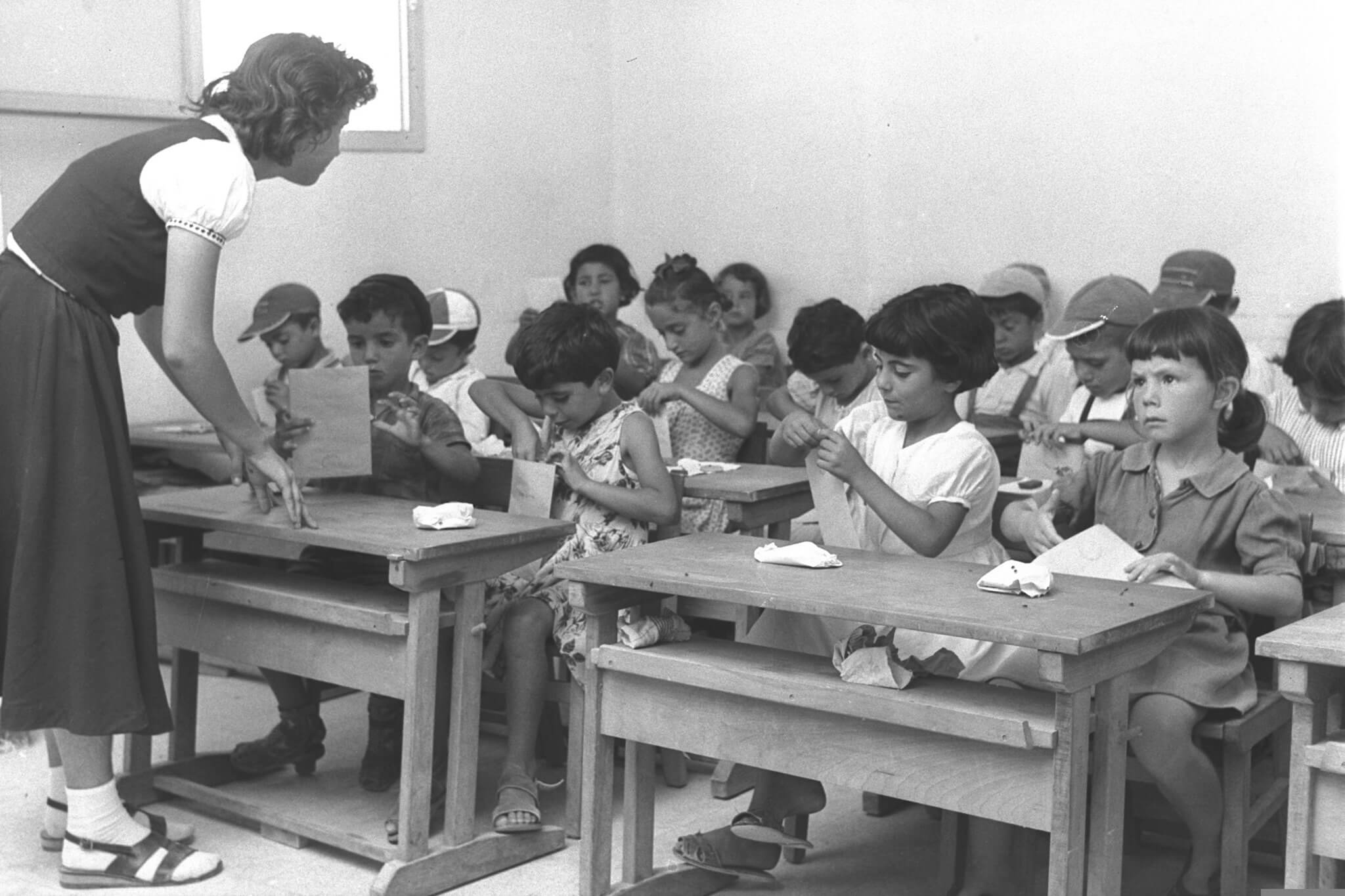

Dr. Tadmor Shimoni researches Hebrew and Jewish education in the Land of Israel from the Ottoman period to the 70s, focusing on the interface between public, academic and educational discourse. Her latest research, which won a grant from the National Science Foundation, deals with the elementary school teachers who immigrated to Israel in the mass immigration of the 20s, immediately after the establishment of the state; 50% of them came from Europe (most of them were Holocaust survivors) and 70% from Islamic countries, mainly Iraq. "A fifth of all teachers in the State of Israel in the 30s were immigrants. I asked to check how their lives and status, as well as the entire education system, were affected by this. For the most part, teachers are part of the backbone of society, natives of the place, speakers of the language, steeped in tradition and culture. And these were people who came from outside, went through immigration processes and changes in society, and at the same time represented the country. That is, immigrants and representatives of the establishment. They are absorbed and absorbed," says Dr. Tadmor Shimoni.

How did this situation arise? As mentioned, in 1949 the Israeli Knesset passed the Compulsory Education Law and thus the state began to provide education for all Israeli children. At the same time, the mass immigration to the State of Israel began and the education system grew threefold within a few years. This created a huge shortage of teachers and the state began to recruit high school graduates, female army teachers and seminarians for this position. When even these did not meet the quota, the state began recruiting immigrants who had graduated from high school or were teachers in their countries of origin and put them through an accelerated course (of several months) where they studied Hebrew and subjects such as the Bible, mathematics, history and geography. At the end of the course, the immigrants began to teach and during their vacations, they passed further exams. When they finished them after a few years, they received a certified teacher's certificate. That is, due to the severe shortage of teachers, in the first years the immigrants taught without being qualified to teach according to the accepted definition. Half of them taught in the periphery - in development towns such as Shlomi, Dimona, Kiryat Shmona, Beit Shean, Ofakim and Moshivi Olim - where new schools were established that needed a lot of manpower. And the veteran teachers, including those born in the country, taught mainly in schools in the center of the country, which also had a significant shortage of teachers.

In order to check how this story of immigration affected the lives of the immigrant teachers, their status and the level of education, Dr. Tadmor Shimon examined statistical data from the Ministry of Education found in the state archives (for example, on the number of immigrant teachers, their countries of origin and years of education); and data on the education system, interviews with the immigrant teachers and memoirs they wrote that are found in local archives (of cities such as Beer Sheva and Kiryat Shmona).

The researchers examined statistical data from the Ministry of Education, and data on the education system, as well as memoirs of the immigrant teachers.

This is how she discovered, among other things, that the immigrant teachers also functioned as social workers (for example, wrote letters to the authorities for the students in their language), and mediated the rules of the establishment to the students. In their memoirs, they mainly emphasized the therapeutic aspect of their work and the success of their students. In addition, it was found that the immigrant teachers from Iraq who taught in Kiryat Shmona, Shlomi and Dimona became principals within ten years.

"It is true that the immigrant teachers were trained less than the veteran teachers, and their Hebrew was less good, but they went through empowerment processes by virtue of their position, felt valuable and significant, mainly because they cared for others. Without them, many children would not receive an education. Because they were more familiar with their norms, culture and language compared to the old teachers. Those children suffered from language barriers, abandonment and poverty, and the immigrant teachers were for them a positive model that could be identified with. However, it is difficult to check how the teaching of the immigrant teachers affected the education of the students in the long term, since there were no high schools until 1962. At the end of elementary school, the children went to work," notes Dr. Tadmor Shimoni.

In terms of the status of the immigrant teachers, the researcher explains that "in the 50s, the economic situation in the country was very bad and most of the immigrants, the immigrants, like immigrants from other societies, worked as manual laborers. The immigrant teachers, on the other hand, got a white-collar job, integrated into the middle class, gained job security and had a professional union behind them. In this way, their socio-economic status was strengthened and their assimilation into society was successful and very fast compared to other immigrants."

It is therefore understandable that this is an extraordinary story about immigration and its educational-social impact. Compared to the current reality, the researcher points out that "today the problems in the education system are mainly the outdated methods and the overcrowded classrooms. The professional freedom of the teachers is limited, the system does not express confidence in them, as manifested for example in the introduction of curricula by parties outside the Ministry of Education, and to a large extent turns them into a kind of officials. Therefore, their authority and influence are decreasing and they are going through the opposite process of empowerment. In the past they were allowed to express a variety of voices and the content was delivered differently by each teacher. For example, there were teachers who taught the Bible in the secular version and others taught in the religious version, as a result of their faith. Today, teachers are more afraid to express their opinion and this affects the educational methods and content."

life itself

Tali Tadmor Shimoni, resident of Lehavim, mother of two adult sons, married to a scientist in the field of computer science. In addition to being the head of the State of Israel Studies track at Ben Gurion University, she is a faculty member at the Ben Gurion Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, and a member of the Nation Building Research Group at the Azrieli Center for Israel Studies (Mali).