250th anniversary of the birth of Alexander von Humboldt, the multidisciplinary researcher who discovered the deep connections of the natural world and was early to identify the damage caused by man

"Nothing stimulated my curiosity like Humboldt's writings," wrote the naturalist Charles Darwin. "I wouldn't have boarded the 'Beagle' or conceived the 'Origin of Species' if it weren't for Humboldt." The great naturalist and father of the theory of evolution was not the only one who was influenced by Alexander von Humboldt. Scientists, artists and even political leaders were captivated by the charms of the energetic naturalist, and incorporated his original and groundbreaking concepts into their works.

Under the ground

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (von Humboldt) was born in Berlin on September 14, 1769 to an upper-class Prussian family. His father was an officer in the court of King Frederick the Great, but died when Alexander was only nine years old. Alexander and his two year older brother, Wilhelm, were left with a cold and emotionally detached mother. Despite her distance, she made sure they received an excellent education from private teachers, and expected them to fill senior public positions when they grew up.

Alexander Humboldt was interested in nature from a young age. He used to collect and classify insects, plants and stones and dreamed of research trips to exotic places, from dense forests to towering mountain peaks. However, his mother was determined to train him for public office, and since he was financially dependent on her, her position was decisive. Humboldt was sent to study political economy and public administration at a small university. Only after a semester did his mother decide that he was eligible to join his brother who was studying law at the University of Göttingen - one of the most prestigious and important universities in Germany. There he actually managed to realize some of his ambitions, and besides languages he also studied science and mathematics.

In 1790 he finished his studies and went with a friend on a four-month journey in Western Europe. In London, Humboldt met with scientists such as Joseph Banks (Banks), the naturalist who accompanied the explorer James Cook on his trip around the world a few years earlier, a meeting that only increased his desire to go out into the big world. But again he acceded to his mother's request, continued to study languages and commerce at the University of Hamburg and from there he applied to the prestigious school for mining studies in the city of Freiberg. It was a kind of compromise with his mother - for her it was an important institution that would prepare him for a career in the government ministry in charge of mining and natural resources. For him it was an opportunity to engage in science, especially geology.

Humboldt was a diligent and energetic student. He used to get up every morning at five, and work non-stop. He finished the three-year study program in eight months, and alongside his studies he found an opportunity to engage in independent research - for example, the reactions of plants to darkness inside the mines.

At the age of 22, Humboldt was appointed a mine inspector - much younger than most of his colleagues. His position allowed him to tour many areas in and around Germany in search of minerals and a survey of mining potential, while the free Arabs were used for his own research in botany, zoology and other fields, and he even published his first articles. Soon he also showed interest in the harsh working conditions of the miners and to improve their safety he developed a mask that made it easier for them to breathe, and an efficient lamp that lit even in the oxygen-poor air deep in mines.

The agony of young Alexander

During this period, Humboldt became interested in a new scientific field - electricity in nature. Scientists then discovered that animals produce and respond to electrical impulses, and Humboldt began to do many experiments on frogs and lizards, hoping to understand the subject. When he did not have experimental animals, he did not hesitate to do the experiments on his own body. He electrocuted himself in various organs, from the skin to the tongue, and carefully recorded his sensations and pains, even when his body was burned and wounded.

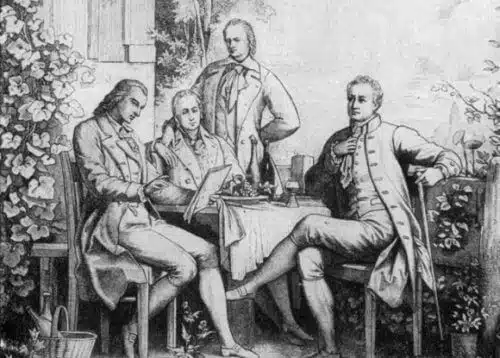

In 1794, while visiting his brother, who lived with his wife and two children in the city of Jena in today's eastern Germany, he met the famous German poet Johann von Goethe, who was himself a passionate naturalist, and even read Humboldt's articles. The two began a burst of joint experiments and research in various fields, mainly botany and electricity, with the energetic Humboldt dictating the crazy pace of work, and Goethe sipping with pleasure from the young researcher's inexhaustible source of knowledge. "A few days with Humboldt are compared to a few years of ordinary life," said the poet. In the following years, they continued to work together at every opportunity and talk a lot, and Humboldt also became friends with Goethe's friend, the famous poet Friedrich Schiller.

During these years, Humboldt's revolutionary view of nature began to take shape. Researchers of his time were generally divided between those who claimed that the animal is in fact a highly sophisticated machine, while others claimed that a living organism is something more complex than a mechanical entity, and that the forces acting within it, such as electricity, cause the whole organism to be something larger and more complex than the sum of its parts. Humboldt applied this point of view to all of nature. He began to think that the whole world is a kind of whole organism, connected by forces. He believed that comparing organisms and geographic regions would help him map broad global phenomena. Humboldt's scientific and philosophical concepts also greatly influenced Goethe's literary work, and were incorporated into his famous play "Faust".

Despite his extensive research in botany and zoology, he continued to excel in his work at the Ministry of Mines, led several very successful expeditions to geological research in Europe and advanced to a senior position.

Discovering America

At the end of 1796 Humboldt's mother passed away. In her absence, he was finally allowed to fulfill his dream and go on real research trips. The large amount of money he inherited upon her death allowed him to even finance such an adventure. He resigned from the Ministry of Mines, and went on a preparatory trip across Europe where he met with researchers from many fields to learn everything he could from them, bought books and scientific instruments, and practiced mountain climbing and using devices such as a sextant to determine the latitude he was in and a barometer to measure altitude.

However, the wars that broke out in Europe following the French Revolution made it very difficult for him to go on the journey he had planned. Countries prevented the passage or movement of citizens of rival countries, and the free ships were used for war needs or to transfer supplies, not for exploration expeditions. In the end he made his way to Paris, where his brother now lived, and was invited to join as a scientist a research trip around the world led by Admiral and explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville (de Bougainville). But due to the French Revolution the trip was postponed and the plans were changed again and again.

In Paris, Humboldt encountered the French naturalist Emma Bonpland, who was supposed to be the botanist and doctor of the trip. The two immediately became friends and discovered many areas of common interest, primarily botany and world travel. When they saw that the journey was delayed, they traveled together to Marseilles, hoping to join Napoleon's forces in Egypt as explorers, but this too was prevented due to a rebellion that broke out in Egypt against the French. They continued together to Madrid, where their luck changed. Humboldt managed to get permission from the royal house for a research trip to the Spanish-controlled areas of South America, which were almost completely closed to foreigners. His mastery of languages, his studies in the fields of commerce and his experience in bureaucratic work in the public sector helped him greatly in obtaining the long-awaited approval, as well as the fact that he undertook to finance the journey himself and bring plants and animals to the royal gardens. After acquiring a lot of equipment and sophisticated scientific instruments, Humboldt and Bonflein boarded a ship in June 1799 for Venezuela.

View from above

For five years, Humboldt and Bonflein toured large areas of South America. They collected plants and animals, and were the first to send to Europe the prepared nut that is now the "Brazil nut". But Humboldt was not content with ordinary biological research. He precisely mapped their location, made astronomical observations, examined soil and rock types, meticulously recorded temperature, humidity and precipitation data, and even tasted the water of the rivers they swam in to compare them. not only this. Everywhere Humboldt tried to compare the general landscape and the nature of the vegetation to what he knew from Europe. In addition to inexhaustible energy and unrestrained curiosity, Humboldt was also endowed with an excellent memory, which allowed him to find everywhere parallels to things he had encountered in the past or similar to them.

Humboldt made an effort to climb as many volcanoes as possible, trying to understand how they are formed, and if a volcano is a local phenomenon, or part of a wider phenomenon - regional, maybe even global. The pinnacle of his ambitions was the inactive volcano Chimborazo, in the Andes Mountains (in present-day Ecuador). The mountain with a height of almost 6,300 m was then considered the highest volcano in the world (today 13 volcanoes higher than it are known, most of them along the Chile-Argentina border - an area that was studied later). Climbing the snowy mountain without proper equipment was arduous and challenging, and the members of the small expedition suffered from altitude sickness, dizziness, cold and injuries. They had to stop about 300 meters below the summit after reaching an impassable area.

The climb to a height of about 6,000 m was apparently a world record in Humboldt's time. No one observed the world from such a height. An ordinary person would admire the view and perhaps notice certain details such as the lack of vegetation above a specific height line. But for Humboldt, the bird's eye view was a moment of inspiration, where the parts suddenly came together into a whole picture, Andrea Wolf (Wulf) writes in Humboldt's biography "The Invention of Nature": "Everything he had observed in the past fell into place. Nature, Humboldt realized, is a network of world life and power. 'He was,' one of his colleagues said later, 'the first to understand that everything is intertwined, like a thousand threads.' This new perception of nature changed the way people understood the world."

Among the things that caught his attention was that plants and mosses in the Andes were very similar to those growing under similar conditions in the European Alps. In his travels he repeatedly noticed such similarities. "Toward the end of his life, Humboldt often spoke of understanding nature by viewing it from a high perspective, from which these connections can be seen," Wolf wrote. "The place where he first understood this was here, on Mount Chimboroso."

human influence

Shortly after climbing Mount Chimborso, Humboldt began to formulate the new vision, which he called "naturgemalde" (naturgemalde) - a German word that literally means "painting of nature", but also aimed at unity and perfection (of nature). He believed that life is everywhere, affected by its environment and influencing it. Humboldt demonstrated the idea with a drawing of a cross-section of Chimborso, in which the exact location of every plant and animal they saw on their way is indicated - from the tropical trees in the valleys at the foot of the mountain, through lower trees and bushes as they progress up the mountain, to the lichens growing right at the snow line. The altitude, the temperature, the precipitation, the type of soil and other conditions affect the mountain vegetation, and hence the animals, while the living creatures affect the mountain itself - the animals fertilize the soil, the roots of the plants penetrate the rocks and hold the soil in place, and even the air is involved in this system, as the wind carries pollen Plants, seeds and insect eggs. Humboldt compared this system to other mountains around the world, showing the common characteristics of similar environmental systems.

Humboldt was not satisfied with the study of nature, in all its components, but tried to study in depth the ancient and contemporary human cultures in the places he reached. He talked to the natives at every opportunity and tried to learn their languages and ways of life, studied ancient cultures, and even almost died when he accidentally touched - for research purposes, of course - curare poison, a deadly nerve poison that the South American Indians used to anoint their hunting arrows with. Unlike most of the white people who came to the area, Humboldt did not treat the natives as savages, but saw them as equal people and even worthy of appreciation due to the way their lifestyle was integrated with nature.

In addition to studying the local cultures, Humboldt also soon noticed the effects of humans, especially the invaders, on the environment. He discovered how humans are depleting natural resources, and that hunting animals can cause entire populations to disappear in a short time. He studied the phenomenon of drying up of lakes and understood how deforestation causes soil erosion which also affects water sources. He noticed that growing the same plant year after year harms the fertility of the soil, and was wise enough to understand that uncontrolled use of natural resources not only creates local damage, but may affect entire systems. He was the first to claim that man's gross interference with nature could even change the climate.

Personal Stories

Another reason for Humboldt's criticism of the Spanish occupation of South America was the attitude of the conquerors to the local inhabitants. He saw how the owners of plantations and mines exploit the natives and employ them in terrible conditions and for meager wages. He met with Simón Bolívar (Bolívar), a native of Venezuela of European origin who was to lead the struggles of the natives against the occupation. Bolivar was very impressed by the European scholar's vast knowledge of South America, and his great love for the continent's landscapes and its nature. He was also greatly influenced by Humboldt's opposition to the Spanish occupation that exploits nature and man, and in their many conversations the seeds of the War of Independence were sown that would be led by the man called "The Liberator", who is still considered the "Father of the Nation" in many Latin American countries.

During his five years of work in South America, Humboldt made sure to send scientists in Europe reports on his research and findings, updates on his travels, as well as plants and animals he collected. Many of them were unknown to science. Among his other achievements, he mapped unknown rivers and waterways, found the magnetic equator and discovered the cold current that runs along the coast of South America in the Pacific Ocean, now called the "Humboldt Current". His essays were published in scientific journals, and reports on his travels - in the popular press.

In 1804, Humboldt returned to Europe, not before visiting the United States and meeting in Washington with President Thomas Jefferson, who was himself an amateur scientist, and was happy to hear about the adventures of the daring explorer in South America and his findings. He arrived in Paris and was received there as a hero. Statesmen and members of high society desired his company, and scientists sought to work with him and learn from him. His lectures attracted large audiences, although he spoke very quickly and jumped from topic to topic at the dizzying pace of his thoughts, and most viewers had difficulty following him.

Humboldt used his fame to travel in Western Europe, where he met with many scientists, continued to expand his knowledge in the study of living and still nature - from climbing volcanoes in Italy to the study of magnetism in various places on the continent. His partner in a large part of the travels and researches during this period was the French physicist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, who is known today as the drafter of the gas laws.

In 1806, Humboldt finally returned to Berlin, mainly under pressure from his brother, who was now a senior diplomat, urging him to return to the homeland. Although he did not want to stay, Humboldt was appointed the court scientist of the King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm III, with a generous salary and no real debts. He continued his research and used the free time to compose articles and books about his travels and research, based on the 4,000 journal pages he wrote during his travels. His great book on South America contained no less than 30 volumes, many of which include paintings and illustrations made by his own hands. One of the most popular among them was the volume on the local cultures, which included many archaeological finds. Even more popular was the book Personal Stories about Journeys to the Equatorial Regions of the New Continent, in which he recounts stories of adventures from his journey, such as fishing for electric eels, meeting face-to-face with a jaguar, sailing rivers infested with crocodiles, alongside descriptions of landscapes, cultures, animals and plants that fascinated readers . Charles Darwin later said that "The Personal Stories" was one of the books that influenced him the most and inspired in him "a burning desire to make even a small contribution to the natural sciences".

The last journey

Later, Humboldt returned to Paris, and although he enjoyed enormous fame, he longed to go on further research trips. His desire was to explore the Himalayas in depth, so that he could compare the vast mountains of Asia with the Andes in South America. For this he had to get the approval of Britain, which ruled India, or more precisely of the "East India Company" - a commercial corporation that ran many businesses in the region and held enormous power - economic, political and even military. However, the heads of the company, who had read Humboldt's articles, his strong criticism of the Spanish treatment of the natives of South America and of slavery in the United States, did not intend to let him see closely the British treatment of the people of India. He met with British politicians and businessmen - but in vain.

When he realized that he would have to give up the dream of the Himalayas, Humboldt decided to go on another exploration, and accepted the invitation of the Russian royal house to explore the Ural Mountains. The Russians hoped that the veteran mine inspector and well-known multidisciplinary scientist would help them find more ways to get rich from their lands. Humboldt - as usual - was much more interested in the overall picture. He invited several scientists from his colleagues to join, and in May 1829 the large expedition, which also included Russian scientists and guides, began the research journey. Humboldt, who was already 60 years old, surprised all the members of the expedition with his physical strength and his vigor while climbing the mountains. After they completed the route approved for them, Humboldt decided to extend the journey, and dragged the entire delegation on an extensive tour of Siberia, without the approval of the authorities. For eight months, the research trip covered about 15,000 kilometers. Compared to the South American trip, Humboldt's Russian trip was much less fruitful, both in terms of scientific findings and literature, although he published the summary of the trip in a three-volume book called "Central Asia", and a smaller book on the geology and climate of the region.

A record of the cosmos

Before leaving for Russia, Humboldt gave a series of lectures at the University of Berlin in which he began to apply the same view from above on the natural world, which allows him to see the uniformity and universality of various phenomena. After his return, he also processed the findings from Russia into lectures, and gradually consolidated the things into a book called Cosmos - the recording of the physical description of the universe that was published in German in 1845 and was soon translated into many languages. He presents the picture of his world in the book, which combines his vast geographical knowledge, and tries to show how the different fields of science meet, and how everything affects everything. He devoted most of his next years to writing three more volumes of "Cosmos", and a fifth volume based on his notes was published after his death.

Humboldt spent his last years in Berlin, in a modest but comfortable apartment, devoting most of his time to writing and meetings with scientists who came from near and far to meet the famous researcher and author. He never married nor showed any interest in women, although many fell in love with him. During his life he had close ties with several young scientists, many of whom accompanied him for a few months. However, there is no explicit evidence that he actually had a relationship with them, partly because he was very jealous of his privacy and destroyed most of his personal letters.

At the age of 87, Humboldt suffered a minor stroke, but recovered. However, his health began to gradually deteriorate, and on May 6, 1859, he died peacefully in his bed, four months before his ninetieth birthday. Humboldt was laid to rest in a state funeral and buried in the family estate near Berlin, as one of the most famous sons of Prussia and Germany as a whole. Few people have been commemorated as widely as him. Many plants and animals are named after him, from penguins and squid to the Humboldt oak that grows in the Andes. Many geographic sites also bear his name: from the Humboldt Mountains in Antarctica to Humboldt Bay in California; From the Humboldt Falls in New Zealand to the Humboldt Glacier in Greenland; From Humboldt Peak in Venezuela to the Humboldt Sea on the Moon; And more mountains, ranges, cities, settlements, districts, universities, schools, parks, ships, research organizations and scientific awards.

In September 1869, huge celebrations were held all over the world in Humboldt's memory, on the 100th anniversary of his birth. In many cities there were processions and parades, events and lectures with the participation of thousands of people, including presidents, kings and other leaders. 150 years later, Alexander von Humboldt remains almost completely unknown, but his profound influence reaches everywhere through the work of scientists and intellectuals who were greatly influenced by Humboldt's breakthroughs: scientific, philosophical and social. Today, when the earth stands on the brink of the point of no return in terms of the destruction that man causes, it is more appropriate than ever to remember the scientist who was the first to understand these effects and warn against them, and perhaps it is worthwhile - finally - to start listening to him.

8 תגובות

Fascinating, I read eagerly.

I read eagerly.

The man got to live an amazing life

I would include his work in the school curriculum.

The world is indeed the result of fields and forces

This article reminded me of Kira Radinsky's research in which she found patterns and connections between phenomena in nature.

Where might this link us?

That our world is a field of information that is mostly still hidden.

Who will be able to discover that hidden area?

By what can we discover that hidden layer?

It's probably still too early to write about what was ahead of its time...

But I believe that just as innovative paradigms and concepts were met with resistance but there was no escape from contracting and replacing the old concept. In a similar way, scientific research will accept the hypothesis that it is not the external variable that we must perform manipulations and changes, but rather the tool that performs the experiment that it is the experimenter himself that will become an experimental laboratory when he changes those parts that make up his desire to receive.

Amazing article. Yes, there will be many more.

It is written: even when his body is burned and wounded.

This is a fragmented sentence. It should probably read:

Even when his body was filled with burns and wounds.

Man is also part of the natural world even if he causes the extinction of most of nature including himself, there have already been mass extinctions of 99% of the living world in the past. Nature will eventually recover and new species will emerge and thrive even if it takes millions of years. In the distant past, the appearance of oxygen from the algae caused the disappearance of most anaerobic bacteria and the appearance of aerobic bacteria, and aerobic respiration developed, followed by man.

Amazing article. I recommend reading.