Weizmann Institute of Science scientists reveal in unprecedented detail how trauma in newborn mice shapes their brains and impairs their social functions in adulthood * A corresponding behavioral expression in humans may take the form of a high level of introversion, social anxiety and an avoidant personality - behaviors known to be characteristic of post-trauma"

The pictures of the children being released from Hamas captivity give hope, but for most of them the release is only the starting point in a long rehabilitation process. Many studies show that exposure at a young age to war, abuse and other traumatic events, may lead to a high likelihood of poor health, social difficulties and mental disorders in adulthood. A new study by Weizmann Institute of Science scientists provides some reasons for optimism. In a study in mice thatPosted over the weekend in the scientific journal Science Advances revealed a team of researchers led by Prof. Alon Chen Which brain mechanisms go awry as a result of exposure to trauma in infancy, and show that these changes may be reversible and treatable early.

Our brain has a wonderful quality, "plasticity" - and it represents its ability to change and learn throughout our lives. However, naturally, in the first years of life, when the brain is still in development processes - plasticity is at its peak. This is true for our language acquisition abilities, but also for our hypersensitivity to traumatic events that may leave a mark that will only intensify in adulthood. Despite the abundant research evidence for this, very little is known about how exposure to trauma at a young age affects different cell types in the brain and the communication between nerve cells in adulthood.

Prof. Chen's laboratory in the department of neuroscience at the institute specializes in the study of the brain and behavioral mechanisms of the stress response. In previous studies we tested in the laboratory How exposure to stress during pregnancy affected mouse fetuses in adulthood. In the current study, the researchers focused on the impact of traumatic events shortly after birth. To offer a leap forward in understanding the impact of trauma on the developing brain and the consequences of this impact in adulthood, the researchers, led by Dr. Aron Kos, combined three of the strengths of the research in the laboratory: the ability to reveal molecular processes in the brain at the highest resolution possible today, by sequencing the genetic material in the tissues at the individual cell level; The ability to use cameras to monitor dozens of behavioral variables in a highly stimulating social environment that simulates natural living conditions as closely as possible, and the ability to process the enormous amount of data received from this environment using machine learning and artificial intelligence tools.

The comprehensive behavioral mapping revealed that mice that were exposed after birth to a traumatic event - neglect on the part of their parents - exhibited a variety of behaviors that indicated their position at the bottom of the social ladder. "A corresponding behavioral expression in humans may take the form of a high level of introversion, social anxiety and an avoidant personality - behaviors known to characterize post-trauma," says Dr. Juan Pablo Lopez, formerly a post-doctoral researcher in a joint research laboratory for the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in Munich, and currently head of a research group in the Department of Neurobiology at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

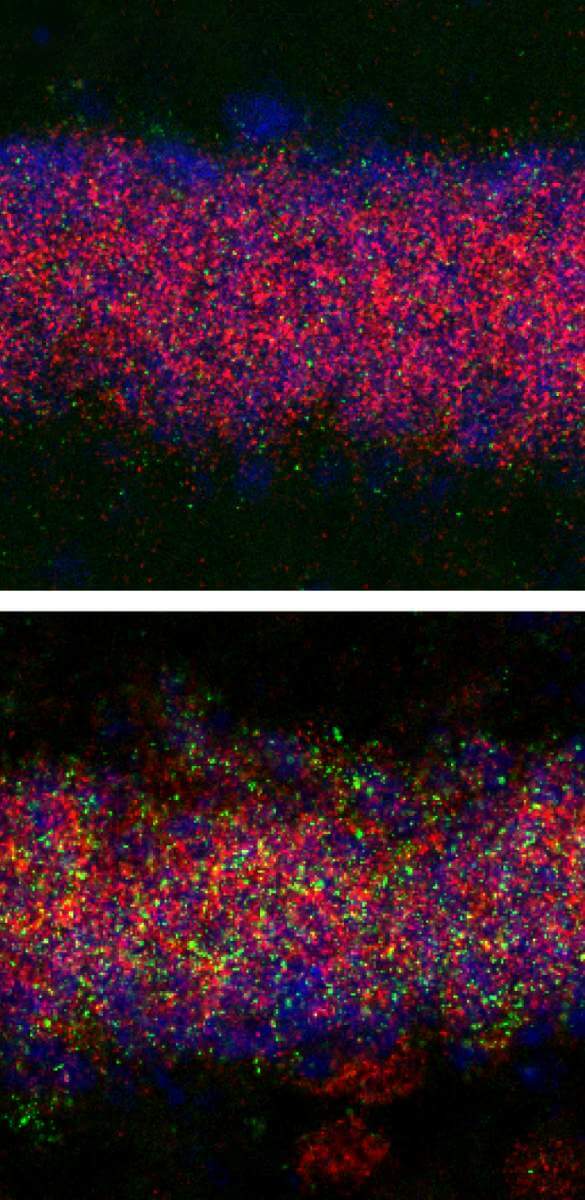

In the next phase of the study, the researchers exposed some of the mice that were subjected to traumatic events in their infancy, to a stressful social event in their adulthood - bullying by other mice. Thus, four groups of adult mice were created: mice that were not exposed to trauma at all; mice that were not exposed to trauma at a young age, but were subjected to bullying in adulthood; Mice that were exposed to trauma at a young age only, and mice that were also exposed to trauma at a young age and were subjected to bullying in their adulthood. To reveal what goes wrong in the brain as a result of exposure to early trauma and what happens as a result of this in adulthood, the researchers created careful comparisons between the four groups by sequencing RNA molecules at the single cell level in the brain region known for its importance to social function - the hippocampus. The comparison revealed that the early trauma left its mark on different cell types and mainly affected the levels of gene expression in two subpopulations of nerve cells: cells belonging to the excitatory glutamate system and the inhibitory GABA system; This imprint was particularly strong in mice exposed to repeated trauma in adulthood.

The nerve cells in the brain communicate with each other through electrical signals - these signals can be stimulating (excitatory) or inhibiting (inhibitory). An excitatory signal encourages communication between nerve cells, while an inhibitory signal suppresses this type of communication. Similar to the gas pedal and brakes in a car, the proper functioning of the brain depends on the correct balance between stimulating and inhibitory messages, and an imbalance in these messages characterizes many psychiatric disorders. One of the ways to measure the electrical activity and the excitatory-inhibitory balance in the brain is through an electrophysiological measurement. To this end, the researchers were assisted by Dr. Julian Dina, a former faculty scientist at the Weizmann Institute and currently an electrophysiologist in the pharmaceutical industry. The electrophysiological measurements in the hippocampus supported the molecular findings: exposure to traumatic events in early childhood disrupted the balance between stimulating and inhibitory messages in adulthood.

Having in their hands a brain mechanism that goes wrong in adulthood as a result of early trauma and is related to the excitation-inhibition balance in the brain, the researchers tried to see if it is possible to repair what is broken. In a short therapeutic window close to the early trauma, the researchers gave the mice a well-known sedative - diazepam or by its trade name "Valium" - which is known to affect the inhibitory GABA system in the brain. The short-term treatment led to no less than amazing results: the treated mice were able to fully escape the treatment or close to it from the behavioral future that was expected of them and from their position at the bottom of the social ladder. "Understanding the molecular and functional mechanisms allowed us to neutralize the negative behavioral effect through pharmacological intervention close to the exposure to the traumatic events. However, this should certainly not be seen as a recommendation for drug treatment in young trauma victims," Dr. Kos clarifies. "On the other hand, the findings do emphasize the importance of early therapeutic intervention for the ability of rehabilitation."

Heavy and continuous stress affects the body at any age and may contribute to the outbreak of diseases - from psychiatric disorders to obesity and diabetes. But in the first years of life, and even before that in the womb, these events have a dramatic effect. "The wars in Israel, Ukraine, Sudan and other countries, the unprecedented global refugee crisis resulting from, among other things, the climate crisis, alongside the growing understanding of the long-term damages of exposure to war and violence at a young age, sharpen the need for better rehabilitation capabilities," says Prof. Alon Chen. "Our new findings indicate a central brain mechanism that is particularly sensitive to childhood traumas, but the most exciting part of the work is the apparent possibility of harnessing the young brain's ability to change for the purpose of rehabilitation from trauma and the costs it may exact in adulthood."

More of the topic in Hayadan: