Researchers at the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine at the Technion demonstrated the brain's ability to trigger disease in the body. They estimate that the discovery may be useful in mitigating negative psychosomatic reactions

Psychosomatic effects are a phenomenon known to all of us. If, for example, we learn that a person we were staying with has the corona virus, there is a significant chance that we will immediately experience a nagging pain in the throat or mild shortness of breath. Already 150 years ago, scientists described how people who are allergic to flowers develop an allergic reaction even to the sight of an artificial flower. Indeed, today it is known that many diseases including allergies, intestinal inflammations and autoimmune diseases may arise or increase due to psychosomatic influence.

How does that happen? How is it possible that a disease is the product of a thought or other brain activity? This is answered by a study conducted at the Technion and published in the journal Cell. The bottom line: The brain can indeed produce actual disease. The research was conducted by the group of Prof. Asia Rolls from the Rapaport Faculty of Medicine, led by PhD student Tamar Koren and in collaboration with Prof. Kobi Rosenblum from the University of Haifa.

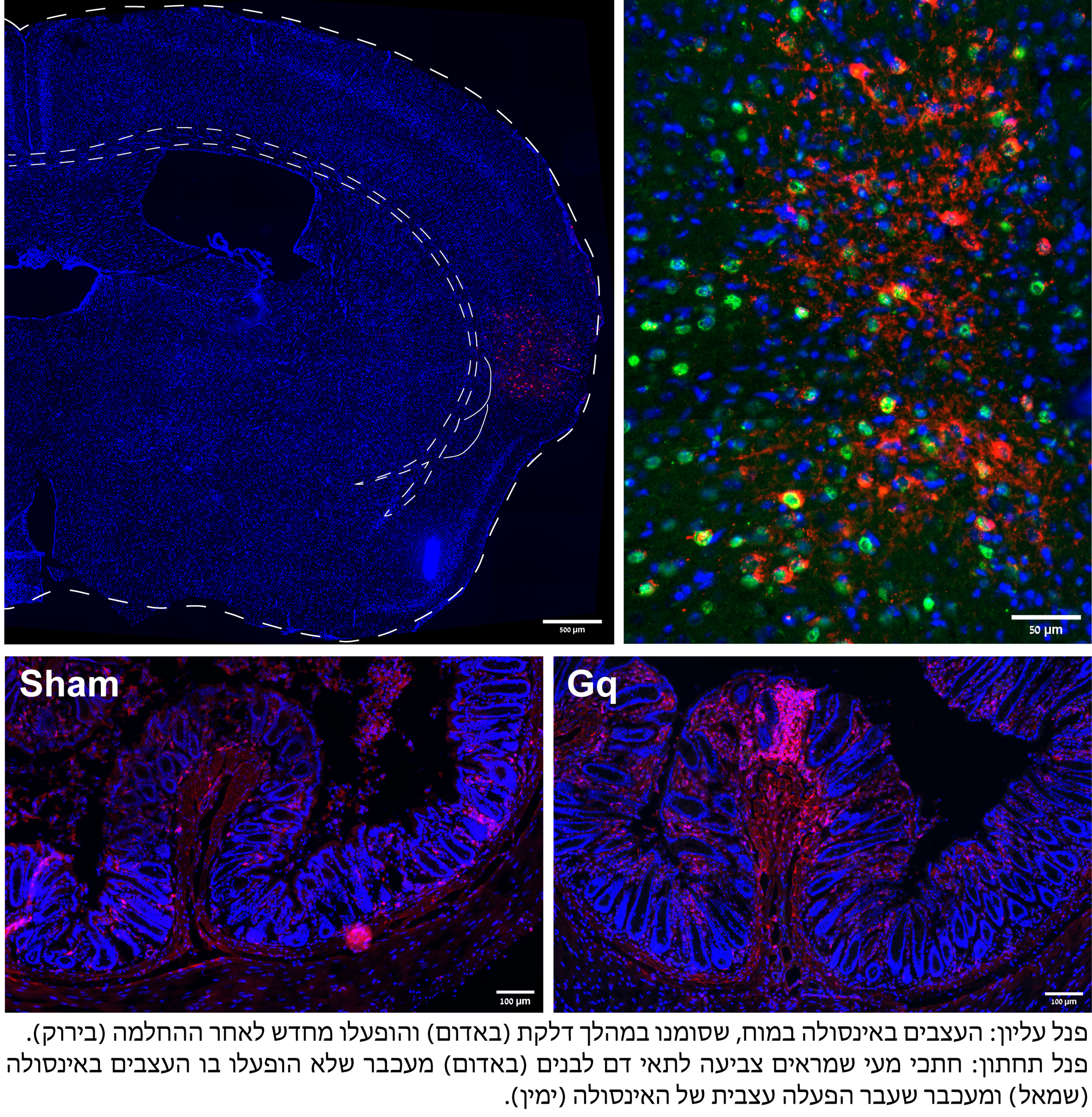

The study focused on an area in the brain called the insula and its connection to intestinal diseases. According to Prof. Rawls, "The insula was chosen due to its diverse roles in interoception - perception of internal physical and mental events and states, including body temperature, breathing, heart rate, pain and hunger; The intestine was chosen because it is rich in nerves - the digestive tract has about half a billion nerve cells, more than the spinal cord. Since the insula monitors the state of the body, we hypothesized that it also stores information about its immune state and that this will have an effect on the state of the intestine."

Indeed, the researchers were able to show that in the case of intestinal inflammation, the insula gathers a lot of information about the dynamics of the inflammation; Moreover, says Prof. Rolls, "we showed that by proactively activating the same area in the insula that was activated by the inflammation in the past, it is possible Produce A new infection. This is a type of ZSynchronization, because this manipulation only works after some immune event."

The current study expands the term "immune memory" which is known today mainly in the context of vaccines - the ability of the immune system to produce memory cells and antibodies; In an initial encounter with a bacterium, virus or vaccine, the immune system learns the characteristics of the invader and stores them in its own memory cells. This way, the next time, the system will react more quickly and efficiently against components of the same pathogen and you can reduce or prevent morbidity.

The Technion researchers show in the current study, apparently for the first time, that such a memory does not only exist within the immune system, but also in the brain; Because groups of neurons in the brain can accumulate, store and export information related to the immune system. Furthermore, in the hour of truth, when the body is attacked, the brain comes to the aid of the immune system and helps it to respond quickly and efficiently.

The researchers emphasize that the research was done on mice, so one must be careful in its interpretations regarding humans; However, they explain that beyond the scientific achievement - the disclosure of the psychosomatic mechanism - the research findings have clinical potential for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases. This is because by manipulating the insula it is possible not only to initiate and accelerate immune responses but also slow down and calm down them, and at least in the case of intestinal inflammation - to actually withdraw the disease as they showed in a study in mice.

In conclusion, it is possible thatDelay The activity in certain areas of the insula can alleviate physiological diseases that have psychosomatic origins. One of the advantages of such an intervention is that it Focused and synchronized between all body systems; In contrast to sweeping and general treatment with steroids, it allows for targeted treatment.

The study was supported by the European Research Commission (ERC grant), the Prince Center for Neurological Diseases of the Brain and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Prof. Kobi Rosenblum from the Purple Department of Neurobiology at the University of Haifa participated in leading the research.

Prof. Asia Rolls completed her bachelor's and master's degrees in the Faculty of Biology at the Technion. After a doctorate at the Weizmann Institute of Science and a post-doctorate in the department of psychiatry at Stanford University in California, she joined the faculty of the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine at the Technion in 2012. She was elected as a member of the Young Academy of Sciences, won the Adelis Prize for brain research and the Krill Prize on behalf of the Wolf Foundation, an ERC grant and was chosen as one of the 40 leading international researchers on behalf of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

Tamar Koren is a doctoral student in the MD-PhD track, which trains doctors-researchers at the Faculty of Medicine at the Technion. She began her studies at the Technion after receiving a B.Mus degree with honors as a violinist at the Buchman-Mehta School of Music at Tel Aviv University. In 2016, she joined Prof. Rolls' laboratory and since then she has been focusing on the research that is now being published, at the same time as her clinical studies in medicine.