From depression and anxiety to diabetes - health conditions resulting from chronic stress affect women and men differently. New study in mice maps at the single-cell level molecular differences in the stress response in the brains of females and males, and may pave the way for personalized treatments

Excellent science needs diversity - scientists from different backgrounds and with different perspectives on reality. But the need for diverse science does not stop at the laboratory gates: the overwhelming majority of research in the life sciences is carried out even today only in male mice, and this may impair the quality of the science and the findings, and the ability to extrapolate from them to humans. A new study by Weizmann Institute of Science scientists faces the challenge and reveals in unprecedented detail the brain differences in the stress response between mice and rats. in research published in the scientific journal Cell reports Researchers from the laboratory of Prof. Alon Chen - a joint research laboratory for the Weizmann Institute and the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in Munich - that a subset of brain cells reacts to stress quite differently in males and females. These findings may contribute to a better understanding of health conditions affected by chronic stress, such as anxiety and depression as well as obesity and diabetes, and even pave the way for personalized treatments for these conditions.

Many of us are under chronic stress, and the resulting morbidity is constantly increasing and is a significant social challenge. These health and mental conditions do affect both men and women, but not necessarily in the same way. Despite many evidences of differences in how men and women deal with stress, there is still no good understanding of the reasons for these differences - and in any case there is no ability to offer personalized treatments for men and women. But in Prof. Chen's laboratory, which specializes in the study of the stress response, they hypothesized that innovative research methods might change the picture. While previous studies found some evidence of differences in the stress response between males and females, these findings were achieved using research methods that may mask significant differences in the responses of specific cells and even erase the effect of relatively rare cells altogether. In Prof. Chen's laboratory, on the other hand, innovative research methods are applied that allow brain function to be analyzed with an unprecedented resolution - at the single cell level - and therefore may shed new light on the differences between the sexes.

"Our findings emphasize that when it comes to health conditions affected by stress - from depression to diabetes - it is highly desirable to take into account the gender variable"

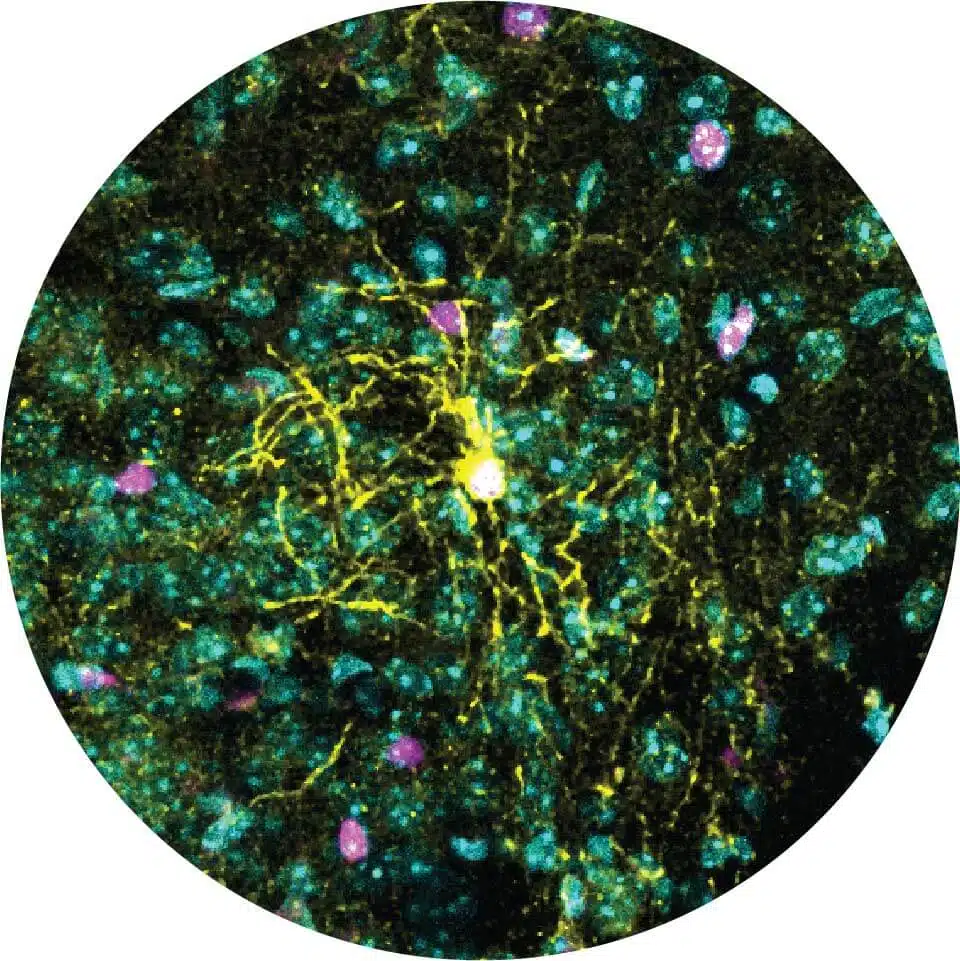

"We directed the most sensitive research lens today to a brain area that is the main coordinator of the stress response in mammals - the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in the hypothalamus," says Dr. Elena Bribio, who led the study. "By sequencing the genetic material in this region at the single cell level, we were able to map the stress response of mice and rats along three main axes: how each cell type in this brain region responds to stress, how each cell type responds under conditions of chronic stress - and how this response varies between species ".

In total, the scientists mapped gene expression in more than 35,000 individual cells - a huge amount of data that provides an unprecedented picture in the scope of the stress response and the differences in the perception and processing of stress between males and females. As part of the study, and in a manner consistent with the principles of open science, the researchers decided to present the complete detailed mapping within Dedicated interactive website which went live at the same time as the scientific publication and will make it possible to access the information in a friendly and convenient way. "The website will allow, for example, researchers who focus on a certain gene to see how the expression of this gene changes in a specific cell type in response to stressors, in males as well as in females," Brivio explains.

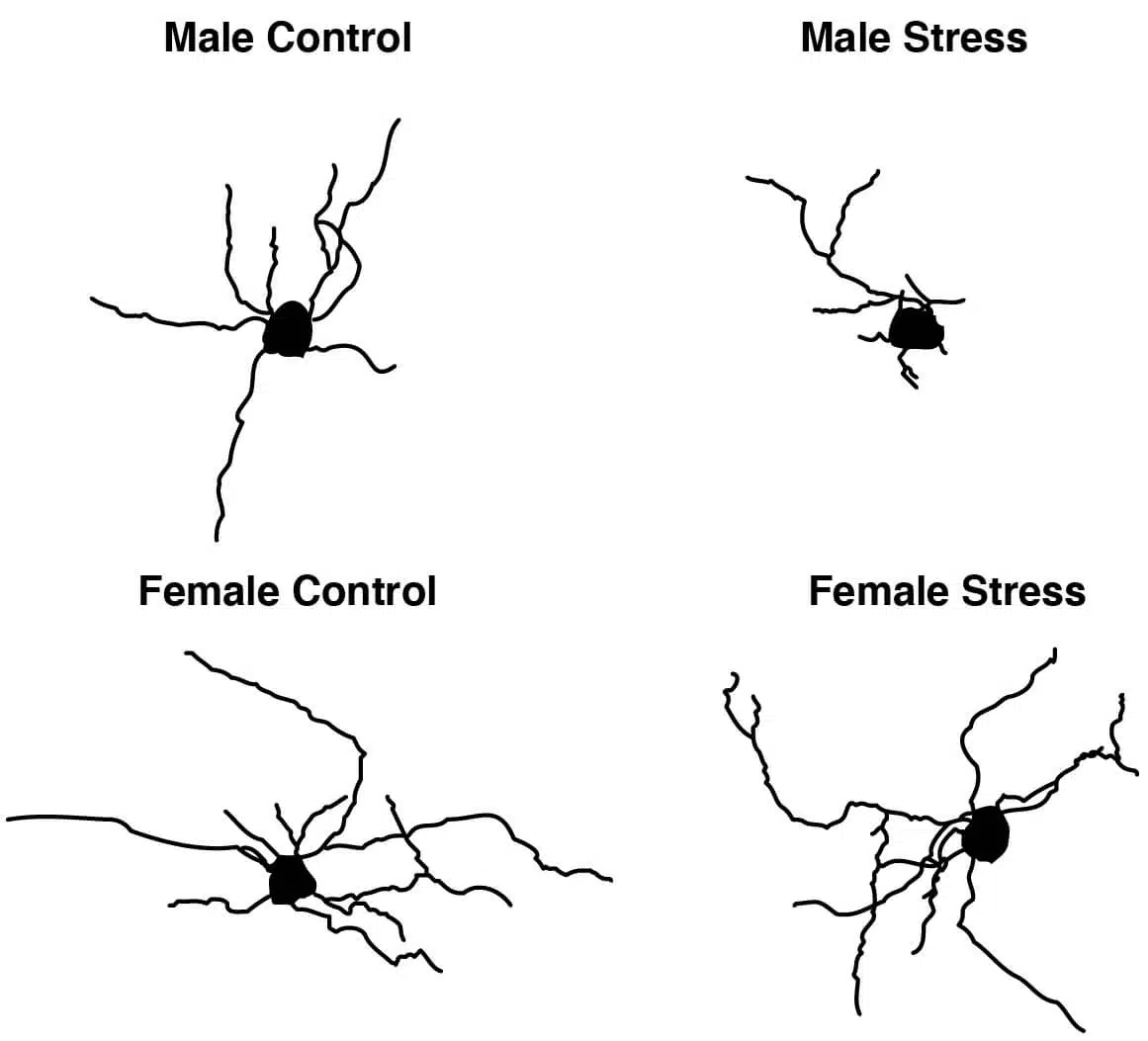

The comprehensive mapping has already allowed the researchers to identify a long series of differences in gene expression - both between males and females and between point stress and chronic stress. The data revealed, among other things, that certain cells in the brain react differently to stress in males and females - when some were more sensitive to stress in females, and some in males. However, the most striking difference was in the type of brain cells called oligodendrocytes - a subtype of glial cells that support the nerve cells and play an important role in regulating brain activity. In males, exposure to stressful conditions, and even more so to conditions of chronic stress, changed not only the gene expression in these cells and their interactions with the surrounding nerve cells, but also their structure. In females, on the other hand, no significant change was recorded in these cells and they were not sensitive to exposure to stress. "Nerve cells attract most of the scientific attention, but make up only about a third of brain cells. The method we applied allows us to see a much richer and fuller picture - to see all the types of cells and their interrelationships in a certain brain region," says Dr. Juan Pablo Lopez, a former postdoctoral researcher in Prof. Chen's group and currently head of a research group in the Department of Neurobiology at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

This variety is basic

Until the XNUMXs, clinical trials of new drugs were done only in men. The thought was that the inclusion of women is not required and is only expected to complicate the research set-up and add variables such as the menstrual cycle and hormonal changes. In pre-clinical experiments performed on animals, the inclusion of females was avoided until the last few years for the same reasons. It is now known that the variation among males, both at the molecular and behavioral level, is often greater than among females, and therefore they are not expected to complicate the research set-up more than males. And still in basic science it is accepted even today to perform experiments on males only. "Our findings emphasize that when it comes to health conditions affected by stress - from depression to diabetes - it is very desirable to take into account the gender variable, as it has a significant effect on the functioning of various cells in the brain under stressful conditions," says Prof. Chen. "Even when the research does not necessarily focus on the effect of sex, and especially in the neurosciences and behavior, it is important to include females in the research system, just as it is important to apply more sensitive research methods - in order to reach a picture of reality that is as complete and rich as possible," Brivio adds.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- A national study showed that more than half of Americans suffer from depression

- Each and every cell is stressed: first mapping of the "stress axis" at the individual cell level

- What did the first students who were exposed to Facebook experience?

- The mathematics of depression

- For the first time: scientists from the Hebrew University have found a gene that determines our sensitivity to chronic pain