The Technion researchers and their colleagues abroad: It is possible that the cellular mechanisms that enable the fusion of the sperm and the egg were created as early as 3 billion years ago in single-celled organisms of the archaea type

The process of sexual reproduction, known to us from the human species as well as from other animals and plants, requires the fusion of a sperm and an egg. The appearance of sexual reproduction is usually dated to about 1-2 billion years ago, but researchers from the Technion and abroad are now hypothesizing that the mechanisms that enable the fusion between sperm and egg appeared as early as 3 billion years ago.

the research on the subject, published inNature Communications. Led by Prof. Benny Podbilevich and PhD student Xiaohui Li from the Faculty of Biology at the Technion with researchers from Switzerland, Uruguay, Sweden, France, Great Britain and Argentina.

In sexual reproduction, each sex cell (sperm or egg) contains half of the genetic information needed to create an offspring; The fusion between the sperm and the egg marks the beginning of embryonic development. This process is carefully controlled, since disruptions in it - for example the fusion of several sperm cells with one egg - can be fatal. That's why evolution developed dedicated proteins called fusogens, which are on the membrane of the mating cell at the right time and place to allow proper fusion.

The laboratory of Prof. Binyamin Podbilevich from the Faculty of Biology studies phosogens from a variety of organisms. After studying and deciphering fusion proteins in nematodes (EFF-1 and AFF-1 proteins), she deciphered their counterpart in plants (GCS1/ HAP2). Thus it became clear that a wide variety of organisms are aided by phosogens that share a very similar spatial structure. This family of fusion proteins was named fusexins and includes representatives that also originate from viruses, animals and single-celled organisms.

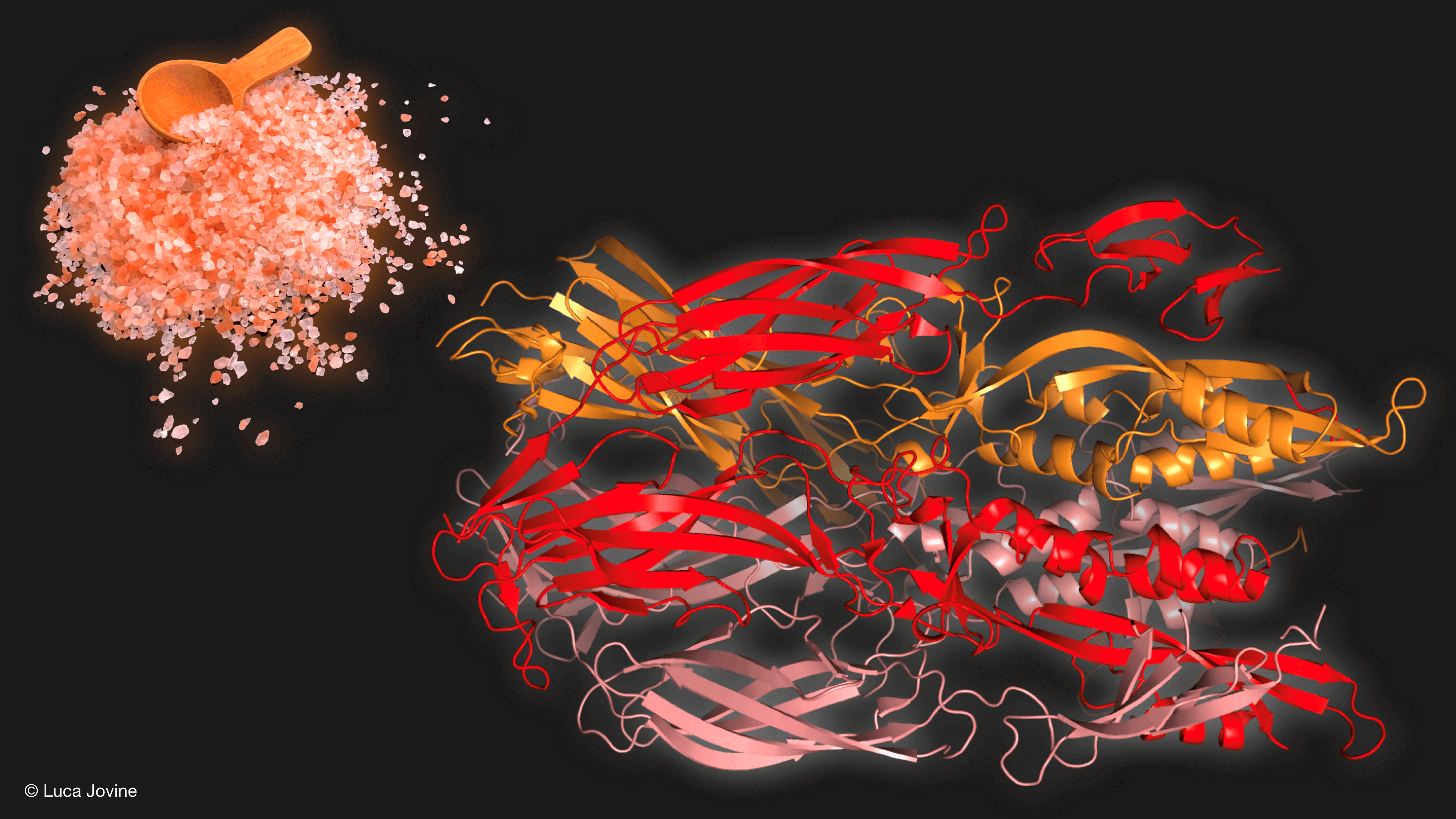

In order to characterize the origin of the phosogens belonging to the phosaxin family, Prof. Podbilevich's colleagues, David Moi, and a joint team of researchers from Argentina and Switzerland conducted a scan of genetic sequences sampled from a variety of sources, including soil, groundwater, salt lakes and the seabed. The researchers discovered in the archaea-derived sequence characteristics that hinted at similarity with genetic sequences belonging to known fusion proteins. They named the gene sequence fusexin1 (fsx1). An expert team led by Pablo Aguilar, Héctor Romero and Martin Graña confirmed that this is a fragment from an archaeon, and estimated that fsx1 belongs to an evolutionary lineage that originated about 3 billion years ago. However, the following questions remain: is it indeed a sequence that creates a protein, is its structure similar to phosogens from the phosoxin family, and is it capable of functioning in cellular fusion?

To determine the structure of the Fsx1 protein, Shunsuke Nishio (Shunsuke Nishio) from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden used crystallographic methods to analyze the spatial arrangement of the Fsx1 protein and showed that its three-dimensional fold contains three structural parts that are largely reminiscent of proteins belonging to the phosoxin family. Surprisingly, Fsx1 includes a fourth element not found in any known phosgene. Prof. Luca Jovine, who helped decipher the crystallographic structure, used an innovative artificial intelligence software recently published (AlphaFold2) to confirm the resulting spatial model.

To prove that Fsx1, which originates from archaeons, is indeed a cell fusion protein, doctoral student Xiaohui Li from the Podbilevitz laboratory conducted an experiment in which she expressed the Fsx1 protein in a mammalian cell system. In cooperation with the director of the laboratory, Clary Valensi, and the members of the laboratory, Dr. Nicholas Brockman and Katerina Pliak, she showed me that indeed, the protein is able to bring about a fusion between cells that normally do not unite at all. This conclusion suggests that archaea are indeed equipped with the earliest cellular fusion protein characterized today.

Fusion proteins of the fuscine family play an evolutionary dual role in two very different groups in the animal world. In viruses, they mediate the penetration of the virus into the host cell (this is also how the corona virus works), while in eukaryotes (with a nucleus) - plants, nematodes and protists (single-celled creatures) - they play a role in the creation of tissues, in the repair of nerve tissues and in the fusion of Zweig cells.

What came before what? Is a phosogen used for sexual reproduction 'hijacked' by a virus, or is a viral protein used for infection 'adopted' by plants? The research of Moi, Nishio, Lee and others raises a third possible scenario - the origin of all fusxins is in archaea, and from them the proteins diverged for a variety of developmental roles, starting with viral infection and ending with the fusion between sperm and egg, a billion years before the sexual reproduction we know today .

The research was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 program, a Mary Curie grant, the National Science Foundation, and more. Part of the analysis of the samples was conducted at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF).

for the scientific article in Nature Communications.

More of the topic in Hayadan: