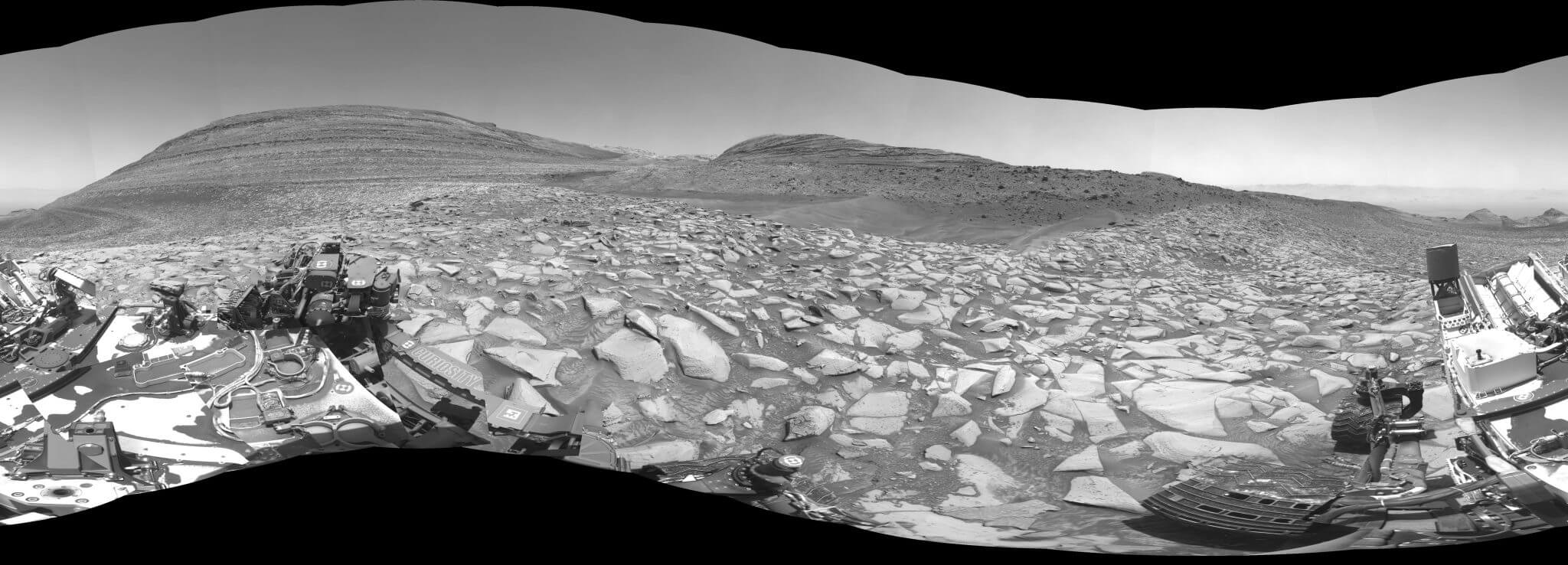

Curiosity has begun exploring a new region that could provide more information about when liquid water finally disappeared from the surface of the Red Planet.

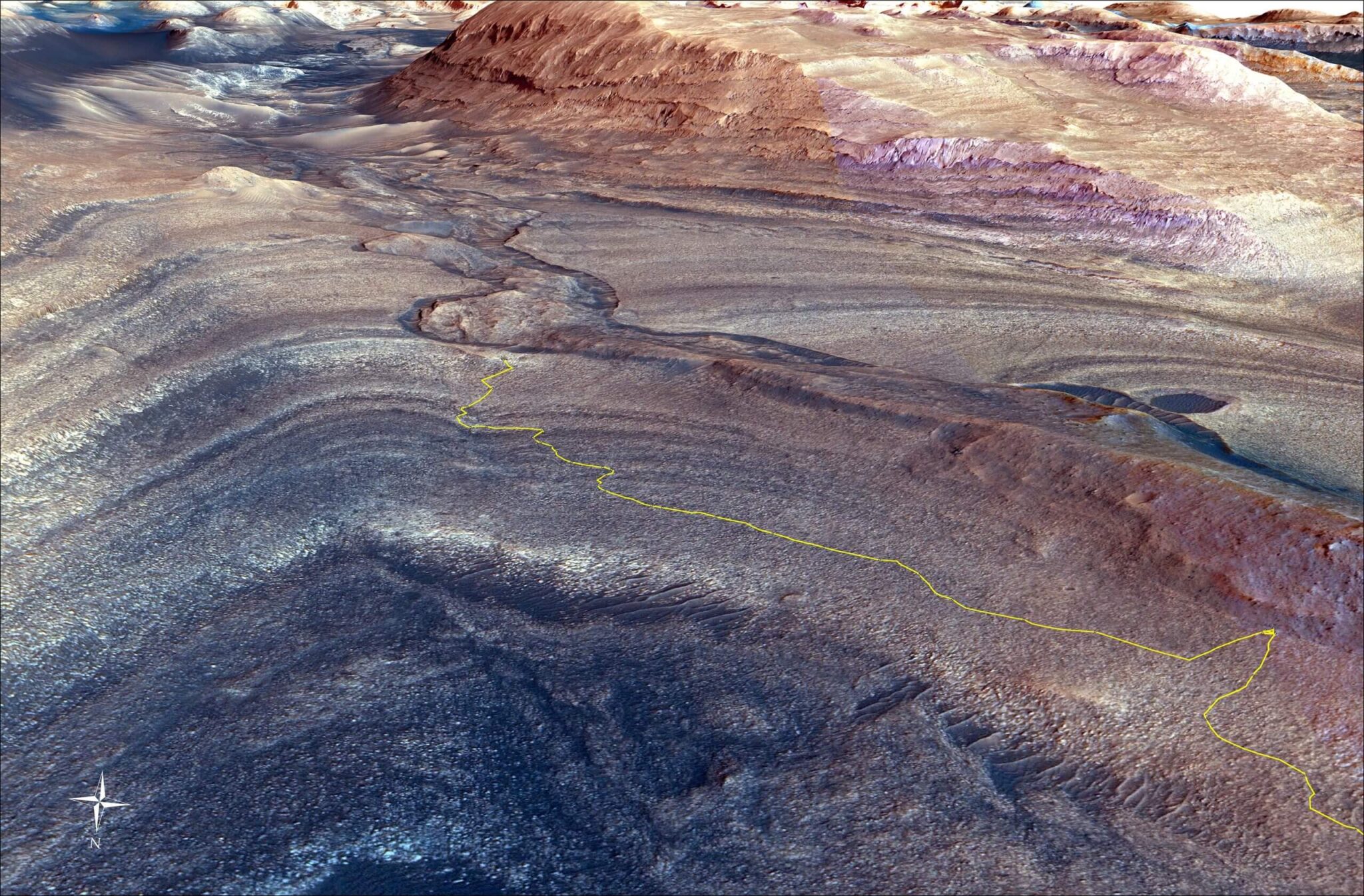

The Mars rover Curiosity has begun exploring a new region, which could provide more information about when liquid water finally disappeared from the face of the Red Planet. Billions of years ago, Mars was much wetter and probably warmer than today. Curiosity is getting a new look at this more Earth-like past as it travels along and will eventually cross the Gediz Vallis – a serpentine, winding landform that, as seen from space, was likely carved by an ancient river.

This possibility intrigues the scientists. Curiosity's team is looking for proof that can verify how the channel was cut into the bedrock below. The sides of the channel are steep enough to rule out, according to the team, that the wind created it. But the flows of a shochut (quick sliding of wet ground) or a river carrying rocks and sediments could have had enough energy to carve into the bedrock. After the channel was formed, it was filled with rocks and poured differently. The scientists are also keen to know whether this material was transported by spillway flows or by dry landslides.

Since 2014, Curiosity has been climbing to the foot of Mount Sharp, which rises five kilometers above the floor of Gale Crater. The layers in this low area of the mountain, formed millions of years ago as the Martian climate changed, give scientists a means to study how the presence of water and the chemicals necessary for life have changed over time.

The full investigation of the channel will take months, and the information the scientists will discover could change the timeline of the formation of the mountain.

After the wind and water deposited the sedimentary layers of the base of Mount Sharp, drift eroded them and exposed the layers seen today. Only after these prolonged processes - and also very dry periods when the surface of Mount Sharp was a sand desert - could the bed of Gediz Vallis be carved.

The scientists think that the rocks and other spills that later filled the trough came from higher up in the mountain, where Curiosity will never reach, and they allow the team to take a look at the types of material that might be up there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PLTiv_XWHnOZpzQKYC6nLf6M9AuBbng_O8&v=XPmVS-ARNPM

"If the channel or spill pile was formed by liquid water, that's really interesting. This means that at a fairly late stage in the history of Mount Sharp - after a long dry period - the water returned, and in a big way," said Ashwin Vasavada, a scientist at the Curiosity project.

More of the topic in Hayadan: