Alexander Wahlberg, doctor of physical chemistry, returned to Israel after years of studying and working in the United States and worked at Kirya for nuclear research. He also insisted on continuing to serve in the reserves, as a patrol officer, and his fall in the Yom Kippur War ended a promising scientific career

"One afternoon I saw Alex taking peace on a small hill and reading a blue book. I approached it and to my surprise I saw that the book was written in English and dealt with chemistry. It really amazed me. To sit during a war and study chemistry," wrote after the Yom Kippur War Yehoshua Messing, a reservist who was stationed in a patrol unit of the Armored Corps at the outbreak of the war, in a letter he sent after the war to Sarah, Alex's widow, he is Alexander Walberg's lieutenant.

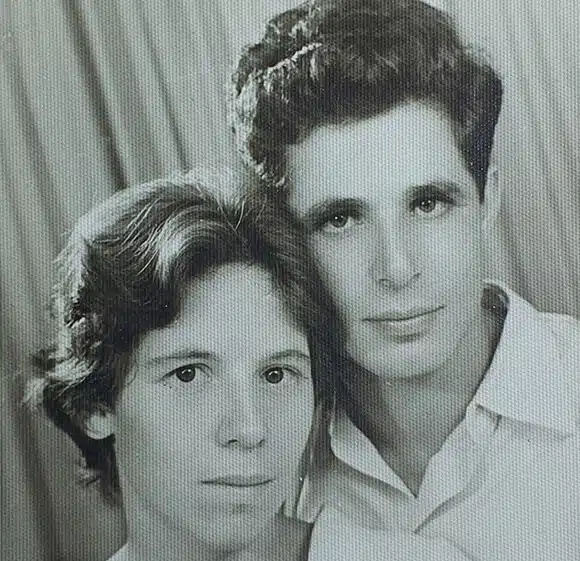

Chemistry in the middle of the war. Alexander Wahlberg at the end of the officers' course, 1956 | Photo courtesy of the Wahlberg family

An unusual childhood

Alexander Wahlberg was born in Tel Aviv on November 20, 1935. His father Yosef was a well-known civil engineer, who won the construction of many well-known buildings, including the Wingate Institute, the Dan Hotel in Tel Aviv, and even the palace of the President of the Ivory Coast. His mother Lydia was also an engineer by training, but after immigrating to Israel from Russia, she could not find a job in that field, and instead engaged in librarianship and was even the chairman of the librarians' association.

His parents divorced when he was a child. During World War II, the mother volunteered for the British Army and was sent to Egypt, where she served in technical positions. At the time, her son stayed in Kibbutz Givat Hasholsha and finished elementary school there. After the war, Alexander and his mother returned to Tel Aviv, where he studied at the "New High School" school and was active in the youth movement "The Olim Camps".

In October 1954, Alexander, nicknamed "Alik", enlisted in the Paratrooper Nahal. He finished a military course, and went on to become an officer. As a young officer he was assigned to the infantry training base. During Operation Kadesh in 1956, he jumped to Sinai with his apprentices, but to his only disappointment, they did not participate in the fighting itself.

In 1957 Wahlberg finished his mandatory service. During the reserve service he was transferred from the infantry to the armored corps, in the position of a patrol officer whose role is to lead troops in the field. At the beginning of his career as a discharged soldier, he went with the members of his movement for a period of work in Kibbutz Gadot near the Syrian border at the time. After that he began to study chemistry at the Technion in Haifa. During his studies, the lecturers at the Technion announced a strike, and to pass the time, Wahlberg joined an Oranim seminar trip. During the trip he met Sarah Rodansky, originally from Tel Aviv who moved to Kibbutz Shaar Golan and was the niece of the well-known theater actor Shmuel Rodansky. They were married in October 1960.

unusual value

After completing their bachelor's degree, in 1962, Sarah and Alexander went to graduate school at Washington University, in the city of St. Louis in the United States. "The goal was to get a master's degree and return," Sarah told the Davidson Institute website, "but friends we met there convinced us that it would be better for him to continue on a direct path to a doctorate in physical chemistry." Wahlberg's research dealt with the characterization of molecules at unusual valence levels.

Every atom - almost - tends under certain conditions to donate or receive electrons, thus becoming an atom with an electrical charge, also called an ion. Usually it is a fixed and characteristic number of electrons for each atom. Iron, for example, tends to give up two or three electrons, which have a negative charge, and thus have two or three excess electric charges, marked as +Fe2 and +Fe3. But ions don't have to be just single atoms. Whole molecules can also have an excess or deficiency of electrons and receive an electric charge, for example the nitrate ion, which tends to have an excess of electrons: -NO3.

Sometimes different ions than usual are formed for certain molecules. In many cases this happens only in the middle of a chemical reaction, a kind of intermediate state that is created during the reaction, and decomposes afterwards. Even if the state is stable or if it is only an intermediate state, it is important for scientists to study these materials, to understand their effect on chemical processes and the possibility of using them in the production of materials.

Materials of great importance to science, industry and agriculture. Wahlberg examines crystals of one of the metallic ions he studied Photo courtesy of the Wahlberg family

New tools

Wahlberg was engaged in the study of such materials, metals with unusual valence levels, that is, metallic ions with different charges than expected. These are usually quite complex ions. In his doctoral thesis, he focused on the study of the -Cr(CN)63 ion, i.e. a chromium atom surrounded by six cyanide groups (a carbon atom and a nitrogen atom), so that the system as a whole carries three negative charges, i.e. an excess of three electrons. This ion is an important component in many materials, including paints, so understanding its chemical behavior is of great importance to chemical industries.

To investigate it, Wahlberg specialized in a technology known as EPR spectroscopy, short for Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. This is a method quite similar to the study of magnetic resonance of atomic nuclei, which is used, among other things, to identify the components of materials, and even forms the basis of the important imaging method called "magnetic resonance imaging", or MRI, which is widely used in medicine today.

The method is based on the magnetic properties of the atomic nuclei. The nuclei of different atoms react differently to changes in the magnetic field that the device creates, and it is possible to measure the resulting change in electrical conduction. In MRI, we focus on the nuclei of the hydrogen atoms, which make up the water molecules in our body, and get images of the tissues according to their water content. In EPR, sometimes called ESR, or Electron Spin Resonance, the effects of the magnetic field are examined not on the nucleus of the atom, but on the electrons around it.

With this method it is possible to study materials that have unpaired electrons, that is, an odd number of electrons in the outer energy level. Wahlberg developed tools that would allow the device to be used to measure and calculate the properties of the -Cr(CN)63 ion. In his doctoral thesis at the University of Washington, he studied in depth the structure of the ion using a combination of EPR and crystallographic methods, that is, an examination of its crystal structure.

The Wahlbergs' three children were born in St. Louis. Dalit, Yossi and Danny. Towards the end of the doctorate, the Six Day War broke out. Alexander tried to get tickets to return to Israel and enlist in the reserves, but on flights to Israel, priority was given to medical professionals and other required professions, and by the time he got a ticket to Israel, the war was already over.

began to make a name for himself in the world of science. Wahlberg in New York during a gathering of chemists, September 1969 | Photo courtesy of the Wahlberg family

Obviously coming back

After completing his doctorate, Wahlberg received a senior research position in the laboratories of the agricultural products company "Monsanto". In recent decades, the company made headlines due to its developments in the field of genetic engineering, and its controversial policy regarding genetically engineered plants, but in the late XNUMXs it focused specifically on chemical pest control products, especially herbicides. Wahlberg's research skills were in demand in the chemistry labs that produced these materials, and he joined the company's research and development department in Missouri. At the same time as his work, he began teaching chemistry at St. Louis University, where he received the rank of professor.

Alongside his research and teaching work, Wahlberg published articles on his work, mainly from the period of his doctorate, in leading scientific journals, such as an article on Cr(CN)63- and its similar ion, CrF63-, an article on the properties of metallic porphyrins - molecules consisting of a ring of carbon atoms and containing Metal ions, which he published with his colleague Yost Manassen (Manassen) from the Weizmann Institute of Science, who stayed for a period in St. Louis, and another joint article on a certain type of such a molecule, a chapter in a book on spectroscopy methods, and more.

In the midst of this professional boom, the Wahlbergs decided it was time to return home, to Israel. "It was clear to us from the first day that we were returning to Israel," said Sarah. "We didn't plan to stay that long, but in the end we were there for nine years." At the end of 1970 Sarah and the children flew to Israel, and a few months later Alexander joined, after completing his professional obligations in the United States. The family settled in the settlement of Omer, near Be'er Sheva, and Alexander found work at the Makhteshim company, which also dealt in pesticides. But quite soon he found a new and challenging employment horizon, in the nuclear reactor.

Scientist and father

"Our department dealt, among other things, with the effects of radioactive radiation on materials, and radiation damage, and I was looking for an EPR expert who would investigate these areas," says Prof. Dan Meyerstein, who in the early XNUMXs was the head of the chemistry department at Kriya for Nuclear Research in Dimona, and later president Ariel University. "Jost Mansin, who was on sabbatical with us, recommended Alex to me, and his resume seemed very suitable for our needs."

Wahlberg began working as a researcher in the chemistry department at Dimona, and at the same time taught at Ben Gurion University in Be'er Sheva. "He was a very intelligent person, with a broad scientific background and a tendency for collaborations," says Meirstein. "I always thought he was a good choice for our department. I guess he deserved to be a full professor, and maybe even further."

At the same time as working in the reactor and teaching at the university, Wahlberg continued to focus on publishing scientific articles. A few days before Yom Kippur 1973, he still had time to sit down with his colleague and friend, Haim Levanon from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and finish the corrections in a joint article they wrote on the use of EPR to study a certain state of porphyrins.

Alongside his many occupations, Wahlberg remembered well his childhood with separated parents and enjoyed being a devoted and involved father in the lives of his three children. "I remember joint trips and outdoor activities with dad," recalls the middle son, Yossi. "He would fly a kite with us, explain to us things like how to bake bread from wheat ears - builds with Legos and patiently answers our questions."

- In the midst of all this, it was important for Walberg to return to serve in the reserves, and shortly after his return to Israel, he already went to reserve service in the Golan Heights.

high spirits

On Friday, the eve of Yom Kippur XNUMX, the family went for a short walk in the Old City of Jerusalem. When they returned home to Omer in the afternoon, Sarah decided it was a great opportunity to take a picture of Alex with the three children. The four of them huddled together on the sofa for a smiling and happy picture. "I remember that afterwards each of us wanted a picture alone with father, and of course he agreed," recalls Yossi, who was seven years old at the time.

The next day, at noon on Yom Kippur, "one of the neighbors came in and told us to turn on the radio, because he knew we knew English and could hear the BBC broadcasts," Sarah recalls. "By the time we got to that, the broadcasts had already started in Hebrew, with the reports about the war. Alik did not wait to be called, but immediately got ready to leave. He said goodbye to the children, and I drove him to the central station in Beer Sheva. The telegram with his enlistment order came only after he had already left for the army."

Walberg served in the war as a patrol officer in the headquarters of the 851st maintenance company, in the 162nd division under the command of Avraham Aden. He commanded a small patrol team that included Yehoshua Messing and Moti Mizrahi. None of them knew each other before the war. The team's role was to lead the maintenance and supply convoys to the fighting forces. In the first days of the war, the team stayed in the Romani region of northern Sinai, a few tens of kilometers from the Suez Canal. "Most of this period was quiet. We were quite far from the canal, and except for two or three airstrikes that did us no harm, it was quiet and the mood was high," Messing wrote to Sarah Wahlberg after the war.

Wahlberg used the time not only to read chemistry books, but also to write letters and postcards home. In addition to update letters to his wife, he made sure to send separate postcards to each of his children, when they were small he wrote in easy-to-read block letters. One day he even managed to find a phone and call home. That is - to the neighbors, because the Wahlberg house did not yet have a telephone line. He chatted briefly with Sarah, and even exchanged a few words with Yossi, who joined her.

across the canal

On October 16, IDF forces began successfully crossing the Suez Canal towards its west bank, inside Egypt. First they crossed on barges, and later they used temporary bridges. "At this point we began to work seriously, to lead ammunition convoys to the bridge over the canal," Messing wrote. "On October 17, a team parallel to us went down and was hit on the axis on the way to the canal. Our team was instructed to replace it. We left at night and started going down the "spider" route. The axis was all full of shell craters and many damaged vehicles. On the way to the bridge there was complete silence. No fire was fired at us and the silence was more frightening."

Traffic jams on the way to the canal: a spider's axis in the era of Suzcha

Clips of the film - Spider's axis in the night of success from hativa 421 on Vimeo.

At the bridge, the team had to wait two hours in a traffic jam created by the large volume of troops that had to cross the canal. "When we were on the bridge, I asked Alex if we should write a will, but Alex laughed and said that he would make sure that we return home safe," Messing said. Further down the road, the jeep got stuck in an obstacle on the bridge. Wahlberg went down to direct him, and continued to cross the bridge on foot, ahead of the jeep.

Late at night the team joined the force that had to be reached west of the canal, in the square of a large building. "We got ready for sleep. It was 1:30. Alex told one of the guys to make a watch list. He went to get his sleeping gear from the front of the jeep. I was standing in the back of it, and then the shelling started. From that moment on, I never saw Alex again," Messing wrote. "I was hit by shrapnel and managed to squeeze myself into the building. Muti went out to look for Alex. I saw him running among the burning vehicles, but he did not find him."

An unfulfilled promise

Alexander Wahlberg was killed by a direct hit by a shell or a Katyusha rocket on the Jeep, on the night between October 18 and 19. The identification of the body took a long time, and only ten days after he was killed did the family receive official notification. "I kept writing him letters all this time. There were all kinds of rumors that they were seen here and there," Sarah said. He was first buried in a temporary cemetery in Bari, and only later was he transferred to his eternal rest in the military section of the cemetery in Be'er Sheva. Among his personal belongings, which were later given to the family, was the wristwatch he was wearing, which still showed the time of the attack: 1:40 a.m., October 19.

At the beginning of 1974, the international journal Chemical Physics Letters published the article Wahlberg wrote with Haim Levanon right before the war. "The journal regrets to announce that one of the authors of this article, Dr. Alex Wahlberg, was killed during the recent war in the Middle East," reads the footnote to the article's title. About a year after his fall, another article of his was published, prepared for publication by his colleague and friend Yost Mansin, based on partial results of experiments that he did not have time to complete.

"Only after Alex's fall did the EPR device that was ordered for him arrive at KMG, so he didn't have time to do any significant work for us," Meirstein said. "We had plans and ideas for collaborations, but since the device arrived late, we could not realize them. He was a very promising researcher, which unfortunately he didn't get to live up to."

Dr. Alexander Walberg, was a true Zionist, who saw working in Kirya for nuclear research not only as an opportunity to do basic research at the forefront of science, but also to contribute to Israel's security and the development of the Negev. He insisted on volunteering for the reserves immediately after his return to Israel, and when the war broke out he left before he was called up. Later, five grandchildren were born to him, which of course he never got to know. One of them received the President's Distinguished Medal at the ceremony of awarding medals to outstanding soldiers at the residence of the President of the State on Independence Day 50, almost XNUMX years after the fall of his grandfather.

For the article on the Davidson Institute website

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- Despite the disaster, the Israeli effort must continue

- One in the mouth and the same one in the heart - the connection between the facial muscles and the heart muscle

- Iran has entered the space club

- Dr. Ariel Heiman was appointed CEO of the Davidson Institute for Science Education

- Compilation of reports from the Technion and the University of Haifa during the Second Lebanon War - July-August 2006

One response

There is a mistake in the title of the article.