Jewish and Israeli traditions and also among the priests and royal people in the Kingdom of Israel, there are differences between them as to the origin of the Israelites - Aram or maybe Egypt?

The story of the Exodus is the dominant narrative in the Pentateuch and it also stands out in the other books of the Bible. Its elements can enlighten our eyes regarding the contradictory traditions that prevailed in Israel and Judah. This narrative is particularly prominent in the Reformed Sefer Devarim, which finds its author from the Israeli Shiloh. But he is not absent from traditions related to Bethel and Jerusalem. The opinions of the authors of the biblical texts were not uniform and they were divided in many areas and especially on the issue of the origin of the Israelites. Some wanted to believe that their origin was from Egypt, from where they were expelled as foreigners, and others knew that their ancestors had always lived between Canaan and Aram.

Israeli and Jewish traditions appear simultaneously in the books of the Bible. Since they were created as folktales, it is not always possible to tell which of them is older and which emerged later. The traditions are described mainly in the books of Exodus and Genesis. Their scope does not necessarily correspond to the size of the population from which they arose, and their occurrence does not correspond to the accepted order of books in the Bible. The legends often reflect contrasting narratives that grew up in the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, but there are also internal Israeli traditions that are parallel to each other, even competing with each other. Conflicting traditions in the Bible also reflect differences between scribes from the king's court versus the writings of priests or prophets.

The earliest information about the Exodus tradition is found in the books of Amos and Hosea who were active in the Kingdom of Israel in the 8th century BCE. This tradition is almost absent from the prophecies of Isaiah ben Amutz and Micah the inheritor who lived in Judah at that time, and from the letters of the other prophets. When the Exodus appears in the prophetic literature from the days of the monarchy, it is mentioned as a symbolic and important collective memory, but not as an actual event. Jeremiah, whose family originates from Shiloh, is the prophet who refers to the Exodus tradition more than any other prophet. At the end of the days of the kingdom, Jeremiah explains to his listeners that the "Exodus from Egypt" should not be seen as an actual event but as a metaphor for leaving exile from wherever it took place:

Behold, the days are coming, says Yahweh: And they shall no longer say, As Yahweh lives, who brought up the children of Israel out of the land of Egypt, for as Yahweh lives, who brought up and brought forth his seed Israel from the land of the north and from all the countries that were driven there and they will live on their land (Jeremiah 23:7-8; 16, yd-tou).

The exodus formula as a metaphor for the exodus: "I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt from the house of slaves" (Exodus 20:20; Leviticus 11), was artificially applied in the Persian period to the autochthonous Abraham: "I am the Lord who brought you out of Ur Chaldeans' (Genesis 15:7).

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah and the Chronicles written in the Persian period ignored the Exodus and emphasized more the tradition of the ancestors and El as the autochthonous ancestral deities.[I] The Exodus did not concern the prophets Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi in those days either.[ii] During the Persian period, the tradition of the exodus from Egypt lost its importance in favor of the autochthonous tradition. We find reinforcement for this approach later in the Hebrew literature from the Greco-Roman period found in the Judean Desert (mainly in Qumran) which does not refer to the Exodus at all.

In its early versions, the story of the Exodus does not resemble the synchronic story in the text of the Masora. It did not include traditions that were added to it over time, such as the tradition of the wanderings in the desert and the giving of the Torah, the eating of manna, the tradition of the Passover sacrifice and the holiday of unleavened bread, and topics such as the firstborn and the Israelites walking in the sea on dry land. These secondary stories developed separately and were added to the original story of the escape from Egypt. Assuming that the composition of the Song of the Sea or "Song of Miriam" predates the 7th century, it turns out that it did not include the splitting of the sea and the Israelites walking through it on land, but only the drowning of the Egyptian army in the sea. A priestly editor made sure to add a concluding sentence in prose to the poetic text: "For Pharaoh's horse and his horsemen came through the sea, and Jehovah caused the waters of the sea to rest upon them, and the children of Israel walked on dry land in the midst of the sea" (Exodus XNUMX:XNUMX). ).

One can be stunned by the fact that in some texts dedicated to the Exodus, and even in the book of Deuteronomy, Moshe's name is absent from them, even though this was requested. In these texts the exodus is attributed to Yahweh and not to Moses, and it seems that the two characters are competing with each other over the question of who brought the Israelites out of Egypt. The book of Deuteronomy cites the ritual proclamation that was said in the temple about the origin of the Israelites: "An Aramean, my father was lost and went down from Egypt" (20:59), but the name of Moses is missing from it. In the book in the priestly wilderness, it was not Moses who brought the children of Israel out of Egypt, but Jehovah's angel: "And our fathers came down from Egypt, and we dwelt in Egypt many days. And they shepherded us from Egypt and our fathers. And we cried out to Jehovah and he heard our voice. And an angel was sent, and we came out of Egypt" (20:15-16).[iii] In the book of Exodus (chapter 3) a detailed scene is described about the working conditions of the Israelites as slaves in the production of bricks. They ask the king for a XNUMX-day leave to go sacrifice to Jehovah their God in the desert. The king refuses and makes the working conditions difficult for them. The negotiations with the king are not conducted through Moses, but through the "Shetri Bnei Yisrael", a type of work managers on behalf of the slaves. Moshe and Aaron are absent from this scene. A late editor who noticed the absence, made sure to add their names at the beginning and end of the story. The original story also did not include an escape from Egypt to freedom from slavery, but only a short vacation to perform a sacrifice to Jehovah in the desert: "And they said: The God of the Hebrews is called upon us. We walked three days in the desert and sacrificed to the Lord our God, lest we be struck by sword or sword" (Exodus XNUMX:XNUMX). Some psalms describing the exodus from Egypt ignore Moses and attribute the exodus to Jehovah:

When Israel came out of Egypt [...]

The sea will see and flee / Jordan will turn back

The mountains danced like deer / Hills like sheep

What are the seas to you, for you will pass away / the Jordan will turn back

The mountains will dance like deer / hills like sheep[…]

Before the Lord, the sick of Oretz / Before the God of Jacob

(Kid Psalms)

The story of the birth of Moses is modeled after a familiar archetype in fairy tales about the humble beginnings of leaders who later rise to greatness. The birth of Moses does not correspond to the stories of the ancestors about the birth of an ancestor to a barren woman who is told about the birth of her son by Yahweh or his messenger, but according to the model of the imaginary birth of Sargon II, king of Assyria (2-705), although it is attributed to Sargon of Akkad. As a result, it is likely that the story could not have been written before the end of the 722th century. The book of Exodus, unlike the book of Genesis, does not include any genealogy, except that of Aaron (chapter 8). Moses, the hero of the story of liberation from slavery, did not beget descendants from whom the Israelites were born, such as the sons of Jacob or the descendants of Abraham. His sons, Gershom and Eliezer, are no longer mentioned in the biblical library and the first is mentioned randomly only in the case of the statue of Micah and the sons of Dan (Judges, XNUMX:XNUMX). Thus one can come to the conclusion that the earliest version of the Exodus tradition did not include Moses and that the hero of the exodus was Yahweh himself.

It can be assumed that the inclusion of the figure of Moses in the story of the Exodus was done by the group of writers from the Shaf'an school only during the Persian period. Thus we find his name mentioned 11 times in the books of Samuel and Kings. Until then, it is doubtful whether the figure of Moses existed. No prophet from the days of the monarchy mentions him, except for a formulaic editor's addition in the book of Micah: "For I brought you up from the land of Egypt, and from the house of slaves I redeemed you [and I sent before you Moses Aaron and Miriam]" (Micah 10:20). In contrast, Isaiah the King mentions Moses twice (XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX), and Jeremiah once. Nehemiah and Ezra do mention it XNUMX times and Chronicles XNUMX times, but only with the term "Torah of Moses". Ezekiel, Haggai and Zechariah from the Persian period ignore him. After Moses was added as the hero of the exodus from Egypt, priestly editors added the Jewish Aaron as a counterweight to the character of the Israeli Moses. Compared to the character of Jacob, who has a large family with parents, a brother, a wife and children who leads the lifestyle of a family man, with feelings, loves and disappointments, the character of Moses is depicted more as a schematic figure that was artificially invented for the needs of a story in which the hero was Jehovah. It should also be noted that "Sinai" is not mentioned in any of the books of the Bible outside of the Pentateuch, except once in the book of Nehemiah. "Sinai" was implanted as an editorial addition in Deborah's song (Judges XNUMX:XNUMX) and in a corresponding psalm in the Psalms (XNUMX:XNUMX, XNUMX), so my conclusion is that it is a fictitious name that has no point in looking for a geographical location.

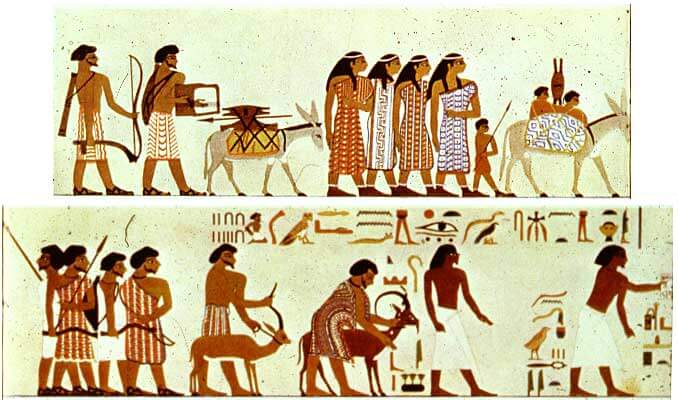

In the 19th century, a population group was discovered in many places in East Asia and in Egypt, called in various variations Khabiru or Afiru, who lived between the 18th and 12th centuries, among the Shumer Akkad population, in the land of the Hittites, Mitani, Nuzi, Ugrit, Egypt and Canaan. Their mention in the beginning of Asia immediately aroused the tendency to identify them as Hebrews in the Bible thanks to the similarity between the names. But today it is clear that the Khabiru/Afiru that were widespread in the ancient world throughout the Fertile Crescent are not Hebrews. In non-Karaic inscriptions Afiru/Afiru are not defined as a people or an ethnic group, but rather as a relatively inferior social class on the fringes of urban culture. We find the Khabiru/Afiru not only in the front of Asia but also at the mouth of the Nile. Leiden papyrus 348 mentions the miners as forced laborers in the temple of Ramses.[iv] But it is clear that the Afiro of the inscriptions of Egypt and Mesopotamia are not the Hebrews of the Bible. On the other hand, the Hebrews in the stories of the Exodus belong to the social category of the Habiru/Afiru and it should not be surprising that they are always mentioned in a negative context. It is not impossible that the Hebrew name is derived from the term Afiro which was still known by the biblical scribes during the royal period and after, when these traditions were recorded in writing.

The fact that the leaders of the Hebrews, Moses and Aaron, were from the tribe of Levi, servants of Jehovah's worship, and that the Hebrews are a type of the Afiru, inevitably creates a connection between the Levites and the class of the Afiru. The Levites were not only a core of the Exodusters from Egypt but all those who wandered in the desert, reached Edom and Medin, adopted the local worship of Jehovah there and became his servants when they arrived as a group of nomads in Canaan. Since they migrated from Egypt to Canaan, they were foreigners without a territory. Therefore, it is not impossible to see the group of Levites who were slaves in Egypt and had no property in Canaan as a type of Afiru. In their new land they connected with the autochthonous Israelites who emerged as a people from among the Canaanites. According to the hypothesis developed, among others, by William Deaver, Shmuel Ahitov and Israel Knohl,[v] The grandiose story spread over four books of the Pentateuch is nothing more than the creation of a "fake national reality", carried out through telescoping. That is, amplifying a marginal or trivial event to an excessive proportion and turning it into a defining event. This is the story of the expulsion of a small group of nomadic slaves from Egypt, their migration to Mount Seir and their arrival in Israel with a new deity: Yahweh. In Canaan, as mentioned, they worshiped a different deity named El, Alion, El Beit-El or El Shadi.

The weakness of the allochthonous tradition in the books of the Pentateuch stems from the fact that it includes an exit but ends without an entry into Israel. This is why another book was added to the large-scale apopha of the Exodus, in which Joshua makes the entry into the land in place of the hero of the exodus, Moses, who remained outside. From the time of the Tel al Amarna letters until the end of the 7th century, Egypt did not play a role in the history of the two kingdoms. It is not impossible that the hatred for Egypt in the four books of the Pentateuch and in a large part of the books of the Bible grew out of the special political situation that was created in the days of Josiah when Assyria was forced to abandon the region and Egypt returned for a while to the front of Asia where it ruled about 700 years earlier.

Studying the textual elements of the grandiose Exodus saga can lead us to the conclusion that originally there was a tradition about a group of Hebrews/Afiru/Levites who fled Egypt and joined an autochthonous population in Canaan. When this tradition was recorded in writing as a short legend, it formed an ideal axis on which many other unrelated stories could be woven. Various authors have added to this short story core, anecdotes from common legends and adapted them to the central axis. It is possible to name a large collection of stories that include the discovery of Moses in the ark of Beor, the magical acts of the ancients of Egypt, the construction of a golden calf in the middle of the desert, the saving of Moses from death before he was circumcised, the revelation of Jehovah on a mountain, the leprosy of Miriam, the marriage of Moses to a Midianite, the rebellion of Dathan and Abiram, the story Korah swallowed by the earth, eating the manna that falls from heaven and the list goes on. These legends originally had no logical or chronological connection between them. This is how a powerful literary work was created that no one could have imagined in advance. A humble story in the beginning became a defining event in the perception of the legendary past of two peoples: Israelis and Jews and subsequently an event of great symbolism in Judaism and Christianity.

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- I found the book of the Torah in the house of Jehovah. Excerpt from the book "The Secret History of Judaism"

- Because this Passover has not been done since the days of the judges

- We did not leave Egypt

- The place and time in which anti-Semitism was born and the connection to the Exodus * An interview with a researcher who published an article about it

- Exodus - invented narrative

- [I] Sara Yafet, Beliefs and Beliefs in the Book of Chronicles and Their Place in the World of Biblical Thought, Mossad Bialik, Jerusalem 1996, pp. 327-322.

- [ii] On the significance of the Exodus in the various books of the Bible, see Yair Hoffman, Exodus in Biblical Faith, University Publications Enterprises, Tel Aviv University 1983, pp. 76-25; Shamai Glander, From Two Nations to One God, Mossad Bialik, Jerusalem 2008, pp. 116-110.

- [iii] Yair Zakovitz and Avigdor Shanan, "Who parted the Red Sea", not so written in the Bible, pp. 49-42. Both authors attribute the absence of Moses not to different and parallel versions of the Exodus legend, but to fear of the cult of personality

- [iv] Roland Enmarch, The Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Lord of All, Griffith Institute, United Kingdom 2006

- [v] William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? What Archeology, Dog Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel, éditions Eerdmans, 2001, p. 121; Shmuel Ahitov, "Rashit Yisrael", Beit Makra 49, 2004, p. 65; Israel Knohl, Where Did We Come From, The Genetic Code of the Bible, pp. 30-19.

4 תגובות

Lenopik. The god Yahweh and his consort Ashtoreth were worshiped by Israel but also by the Midianites and some say the aforementioned - Jordan. See Wikipedia entry.

Two years ago there were still religious people hanging around this portal and commenting and it is better full of commenters. Not anymore now. The separation between religious and secular people, I'm not saying non-believers, happened.

The visa is mentioned in the Temple in Jerusalem by King Manasseh. followed by Josiah who cleansed the statues and issued the visa. According to the archaeologists, statues of him were physically discovered in the Land of Israel and they are not suitable for a spiritual god. In part he looks like a ram and in part as a sexual man.

Hence there was a gradual development to belief in a non-corporeal spiritual god, and it took hundreds of years to burn the statues and idolatry from the people and the temple. And this does not contradict what is written about Josiah and Manasseh. Only that in the sources they clarified less that there were statues of Jehovah and more that there was idolatry. Yes, they specified that she was Ashra, but they did not specify that she was Jehovah's consort. But from the fact that in the days of Menashe there were statues of Asherah in the temple it can be seemingly understood that there were also statues of Jehovah in the temple. And from the fact that there were statues of female gods it can be assumed that she was the consort of a male god. As with the Egyptians and with our ancestors the Chaldeans, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians. The revolution introduced by the ancient Israelites is the belief in an immaterial spiritual God and the unity of reality.

In fact, Pharaoh Akhenaten, the father of Tut Anah Amon and husband of Nefertiti, also tried to bring about a monotheistic reform in Egypt and failed miserably, the people resisted. It is possible that the Israelites are the sect that worshiped one god in Egypt, the god Amon. Those who remained faithful to the one God, and perhaps came out of Egypt. Jehovah's worshipers were called by the Egyptians Yehu, Shesu, and also Israel.

https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%A7%D7%99%D7%A6%D7%95%D7%A8_%D7%AA%D7%95%D7%9C%D7%93%D7%95%D7%AA_%D7%99%D7%94%D7%95%D7%94

https://www.hayadan.org.il/%d7%9c%d7%90-%d7%99%d7%a6%d7%90%d7%a0%d7%95-%d7%9e%d7%9e%d7%a6%d7%a8%d7%99%d7%9d

Your previous article actually.

The archaeological evidence speaks of the development of Israel from the Canaanites and that the kingdom was never united. See Israel Finkelstein's entry. In fact, evidence was found for King David as well as for Jeremiah.

At the minimum level, meaning at worst there is no evidence for the Exodus. The importance of the story is mainly the moral. Of course, this will not be enough for religious people.

Quite a few historians from the narrow school of thought tend to a wrong interpretation regarding the origin of the Israelites as an autochthonous Canaanite population. Here are some counter arguments:

The tribe of Yehuda is mentioned in several Egyptian inscriptions in the 14th and 13th centuries in Egyptian "Shesu Yehu". A tribe of nomads who lived in the past in the southern eastern Jordan in the Sha'ir Mountains.

The tribes of Israel are mentioned in Egyptian inscriptions "Yakobail" past the northern Jordan in the area of Bashan and Gilead.

The name Jacob was popular in the Levant in the 17th and 16th centuries in inscriptions from northern Syria (Padan Aram) and also one of the Hyksos kings was named Jacob-Har and this alludes to the story of Joseph in Egypt.

The god Jehovah was not part of the pantheon of Canaanite idols and is not mentioned at all in the Ugaritic writings.

The biblical Hebrew language was very close to the Moabite Ammonite and Edomite than Canaanite and Phoenician as is expressed in ancient inscriptions from the Levant.

In conclusion, the Israelites and Judah were nomadic tribes that originated in the deserts of the eastern Jordan and Syria and were not Canaanites. Also in the Bible, the common origin of the Hebrews with Moab, Ammon, the sons of Lot, and Edom, the sons of Esau, and the ancient tribes, the descendants of Ketura, was presented.