Negative events in childhood and sleep problems make it difficult to recover from an acute stress disorder and thus increase the risk of a mental disorder

What are the mechanisms that allow most people to be resistant to acute stress disorder and not develop a mental disorder as a result (such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder - PTSD)? And why do these mechanisms not work well for some people? Acute stress disorder develops near and in response to a traumatic event, one that threatens physical or mental integrity - for example, a battle, an accident, an earthquake, rape, boycott and even dismissal.

Prof. Rui Edmon, head of the clinical neuropsychology department at the School of Psychological Sciences at the University of Haifa, together with his team, researches the way in which people react to trauma and the physiological, mental, cerebral, hormonal and emotional mechanisms that allow most of them to cope with it and recover. According to him, "In a series of studies, we discovered that what differentiates people vulnerable to acute stress from those who are resistant to it - is not necessarily what happens during the traumatic event itself, but the way of recovery after it. That is, the way in which the brain and other stress pathways recover (for example, physiological changes such as a decrease in heart rate and relaxation). Thus, for example, a person's mental and physiological reaction during a fight will not necessarily predict his mental and psychological coping with the event later in life. What is more decisive is the manner of his recovery - the amount of time it takes for his mental, physiological, mental, emotional and hormonal state to return to its normal state, as it was before the incident. When this situation does not fully return to normal, the risk of maladaptive activation of the stress response and the development of a mental disorder increases.

In their current research, which is still ongoing with the help of a grant from the National Science Foundation, Prof. Edmon and his team (which includes doctoral students Noa Magal, Sharona Rab and Lisa Simon) are testing whether it is possible to predict how a mature and healthy person will react to future acute stress using indicators from their natural environment. To this end, the researchers fitted sensors to 140 healthy subjects, which regularly recorded and transmitted indicators such as body movements and heart rate. In this way, the researchers could know what the subjects did at every moment in their daily lives - for example, did they walk, sit, exercise, rest or sleep. After a period of time, the subjects arrived at the laboratory (not knowing what awaited them) and the researchers exposed them to acute stress - physical, social and emotional - putting their hands in ice water for ten minutes, cognitive effort (pressure to solve math exercises) and giving negative social feedback on their performance. This round was carried out twice and was followed by another round in which the subjects received positive feedback on their performance. At this stage - the relief stage - the researchers wanted to test the recovery of the physiological, emotional and mental response, which as mentioned in their previous studies they found to be the predictor of resistance to stress. For this purpose, the subjects were given questionnaires that examined their condition and their brains were scanned with an MRI.

Recovery from stress has been found to be closely related to sleep patterns; Subjects whose sleeping routine is not regular (as the sensors testified) - for example, going to bed and waking up every day at a different time - had difficulty recovering from the stress; In the relief phase, they still continued to feel bad emotionally and to feel pressure, as they reported in the questionnaires. "In sleep, cognitive and emotional processing mechanisms take place such as the extinction of fear and consolidation (a process in which information that is in short-term memory moves to long-term memory, for stable and permanent storage), therefore it helps recovery and recovery from trauma and stress. When the sleep is less regular and of good quality - these mechanisms work less well, which causes ineffective processing of trauma and high sensitivity to stress", explains Prof. Edmon.

After discovering the sleep finding, the subjects filled out validated questionnaires that examine negative events in childhood (common in many homes and contributing to high arousal), which can impair sleep patterns, such as an unstable growth environment and low socioeconomic status. It was found that subjects who experienced such negative events and thus were exposed to a lot of stress in childhood developed suboptimal sleep patterns, which, as mentioned, harms cognitive and emotional processing mechanisms. Therefore, they had difficulty recovering from the stress.

There is a connection between negative events in childhood and sleep problems, difficulty dealing with trauma and stress and the development of a mental disorder. This is a hidden vulnerability, that is, we are not aware of it until a trauma occurs in adulthood.

According to Prof. Edmon, "There is a connection between negative events in childhood and sleep problems, difficulty dealing with trauma and stress and the development of a mental disorder as a result. This is a hidden vulnerability, not aware of it until trauma occurs in adulthood. Subjects with suboptimal sleep patterns are both those who reported more negative events in childhood and also those who had difficulty recovering from the stress we caused them. In other words, we found that irregular sleep patterns mediate the relationship between exposure to stress in childhood and poorer recovery from stress in adulthood."

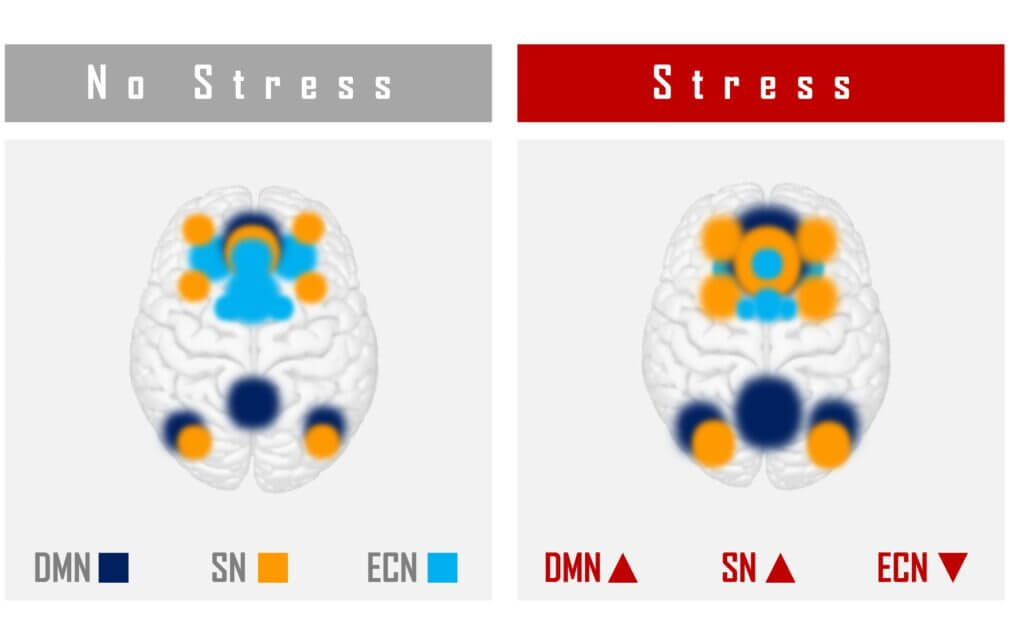

These days, the brain MRI data of the subjects are being examined. In the past, the researchers discovered that during times of stress, the salience network in the brain - which responds to significant events for a person - expands in the cerebral cortex at the expense of the executive functions network (which, among other things, is involved in attention, working memory, emotional regulation and social and academic functioning), and thus impairs its activity and brain recovery suppressor That is, it is a brain pattern that characterizes sensitivity to stress. When the prominence network contracts back after the stress is over, the recovery from it is optimal and complete. Now, based on the subjects' MRI data, the researchers intend to test whether negative childhood events and sleep problems cause a similar pattern of brain activity.

Life itself:

Prof. Rui Admon, 43, married + two children (13, 10), lives in Tamar in the Jezreel Valley. In his free time he likes to work in the garden, travel, go to the beach and swim.