In theory, a male skin cell can be turned into an egg and a female skin cell into a sperm cell. There is also the possibility of a child genetically connected to several parents, or only to one parent

By: Julian Coughlin, Lecturer in Bioethics, Monash University, and Honorary Fellow at the School of Law, Monash University in Australia and Neera Bhatia, Associate Professor of Law, Deakin University in the UK

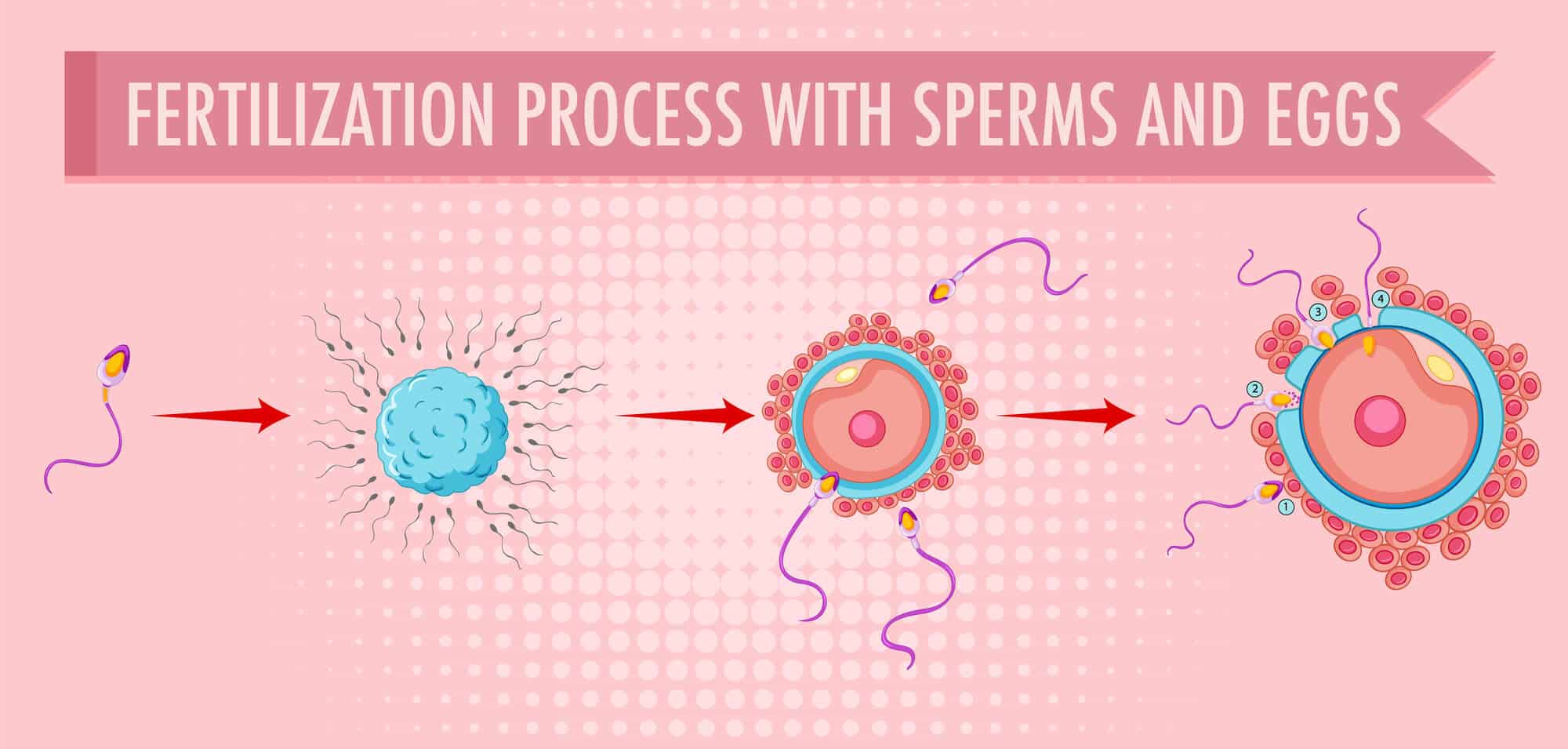

It will soon be possible to turn human skin cells into normal egg cells and sperm cells using a technique known as "gametogenesis in vitro". This involves the creation (genesis) of eggs and sperm (gametes) in a test tube outside the human body.

In theory, a male skin cell can be turned into an egg and a female skin cell into a sperm cell. There is also the possibility of a child genetically connected to several parents, or only to one parent. Some scientists believe that human applications of gametogenesis in vitro are still far from being realized.

However, scientists dealing with human stem cells are now overcoming the barriers. New biotechnology companies are also looking for ways to commercialize this technology.

Here's what we know about the prospects for human in vitro gametogenesis and why we need to start talking about it now.

Is the technology available?

Gametogenesis in vitro begins with "pluripotent stem cells (undifferentiated stem cells)", a type of cell that can differentiate into many different types of cells. The goal is to convince these stem cells to become eggs or sperm cells.

These techniques can use stem cells extracted from early embryos. But the scientists also discovered or found how to return old cells to an unsorted state. This opens up the possibility of creating eggs or sperm cells that belong to an existing adult.

Animal studies have been promising. In 2012, scientists created living mice born from eggs that started life as skin cells on a mouse's tail.

More recently, the technique has been used to promote intersexual reproduction. Earlier this year, scientists created baby mice from two genetic parents after turning skin cells from male mice into eggs. Mice pups with two genetic mothers were also created).

How did scientists breed mice with two fathers?

Scientists have not yet been able to adapt these techniques to create human gametes. Perhaps because the technology is still in its infancy, the legal and regulatory systems in Australia are not concerned with whether and how the technology should be used

For example, the National Research Council and Technology-Assisted Medicine guidelines, updated in 2023, do not include specific guidelines for gametes produced in vitro. These guidelines will need to be updated if in vitro gametogenesis becomes practical in humans.

the potential

There are three prominent clinical uses for this technology:

First, in vitro gametogenesis can simplify the process of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Obtaining eggs today involves repeated hormone injections, minor surgery and the risk of overactive ovaries. In vitro gametogenesis can avoid these problems.

Second, technology can bypass certain forms of medical problems. For example, it can be used to create eggs for women born without functioning ovaries or in early menopause situations.

Third, technology allows same-sex couples to have children who are genetically related to both parents.

Legal, regulatory and ethical issues

If the technology becomes practical, in vitro gametogenesis will change the dynamics of family formation in unprecedented ways. How we respond requires careful consideration.

Is it safe?

Careful experiments, vigorous monitoring and continued accompaniment of each child born will be essential - as was the case with other reproductive technologies, including in vitro fertilization.

Is it equitable?

Additional issues are related to access. It may be unfair if the technology is only available to the rich. Public funding can help - but the question is whether it is right to do so, depending on whether the state should support people's areas of productivity.

Should access be restricted?

For example, in older women pregnancy is rare, mainly because the number and quality of eggs decline with age. In vitro gametogenesis will theoretically make it possible to provide "fresh eggs" to women of any age. But helping older women become mothers is a controversial issue, because of physical, psychological and other factors associated with giving birth later in life.

We will still need a surrogate mother

If we take skin cells from each male partner and create an embryo, a surrogate mother will still be needed to carry the pregnancy.

Who are the legal parents?

In vitro gametogenesis also raises questions about who are the legal parents of the future child. We are already seeing legal discussions related to non-traditional families created through surrogacy, egg donation and sperm donation.

In vitro gametogenesis will theoretically also allow to create children with more than two genetic parents, or with only one parent. These options also require us to update our current daughters on parenting.

How far is too far?

Of the possible uses already mentioned, intersexual reproduction is the most controversial. The reproductive limitations imposed on sexual relations between people of the same sex are sometimes seen as a "social" form of deficiency, which the medical profession is not obliged to correct.

However, the moral implications are virtually the same regardless of whether in vitro gametogenesis is used by same-sex or different-sex couples. These two uses of technology serve exactly the same purpose: to help couples realize their desire to have a child who is genetically related to both parents. It would be unfair not to allow this access to just one of these groups.

But intersexual reproduction is only the tip of the iceberg. In vitro gametogenesis could theoretically enable "single reproduction" by creating eggs and sperm cells from the same individual. It is interesting to note that a child created in this way will not be a duplicate of the parent, because the process of creating gametes will mix the genetic material of the parent and create a unique genetic entity.

Or people can choose "multidimensional parentage" by combining genetic material from more than two people. Imagine, for example, that two couples create embryos through IVF. In vitro gametogenesis can then be used to create eggs and sperm from each of these two separate embryos, which can then be used to conceive a single child genetically related to all four adults.

Finally, in vitro gametogenesis may revolutionize critical genetic selection. We will have many more embryos than in regular IVF to screen for diseases and genetic traits.

Therefore, it will be urgent to discuss "designer babies", genetics and whether we have a moral obligation to give birth to children with the best chance for a good life.

For the article in THE CONVERSATION

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- Things that Yoram knows: sick, dying, widow - why women live longer than men

- A cloning experiment shows that the cancer is reversible

- "Ghost" hearts from a pig and the patient's stem cells will replace the need for heart donations

- For the first time, human skin cells can be directly transformed into cells of a placenta

- Pluristem treated the first three corona patients in Israel with stem cells as part of compassionate care