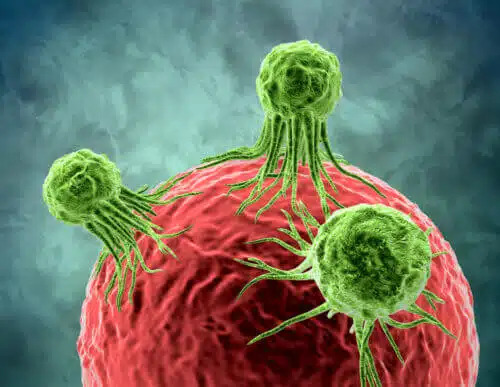

A group of scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science recently investigated what happens to cellular memory in cancer. Their findings illustrate how "memory loss" may affect the course of malignant diseases

Similar to how our earliest memories shape our adult personality, the cells of our bodies also have "memories" that structure their identity. The cellular memories remind our skin cells to remain skin cells and our bone cells to remain bone cells - even after the passage of many generations of cells. A group of scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science recently investigated What happens to cellular memory in cancer. Their findings illustrate how "memory loss" may affect the course of malignant diseases.

"Generally, cancer develops as a result of genetic mutations," says Prof. Loaded condition From the Department of Mathematics and Computer Science and the Department of Biological Control. "However, mutations only partially explain the changes that make cancer deadly." Besides mutations in the genome, there are also epigenetic changes that do not change the genes, but affect the way they are expressed; The epigenetic mechanisms are those that keep some genes from being expressed in certain cells and not in others, and therefore constitute a kind of "cellular memory" that gives the different cells their unique identity. It is known that cancer involves not only genetic mutations but also epigenetic changes, but it is not known if and how cancer cells "harness" the epigenetic mechanisms to their advantage. Prof. Tanai and research student Zohar Meir decided to get to the root of the matter.

In order to study cellular memory in cancer, Prof. Tanai and Meir developed a modern version of a classic experiment. In the XNUMXs, Salvador Luria and Max Delbruck studied genetic mutations in bacteria. Luria and Delbrook tried to understand why when bacteria grown in the laboratory are exposed to viral infection, some survive, while others die. They grew bacterial colonies, each originating from a single cell, and after many generations of bacteria tested the ability of the colonies to survive a viral infection. The results were amazing: most of the inhabitants of the colonies did not face the viral infection at all, but in each colony, a small subgroup, each consisting of millions of cells derived from a single bacterium, showed almost complete resistance. This finding led them - and following them, the entire young field of molecular biology - to understand some of the basic mechanisms of genetic inheritance and to focus on DNA as the main carrier of the genetic information in the cell.

Two generations later, the institute's researchers grew cancer cells instead of bacteria for six months. They started with a few hundred individual cancer cells which they each grew individually to produce many colonies of cancer cells. To check how well the new generations have preserved the memories of the original cancer cells, the research team used cutting-edge methods of sequencing the genetic material at the single-cell level (single-cell sequencing). While Luria and Delbrook tested a single trait in each colony, Prof. Tanay and Meir were able to measure the RNA molecules produced from thousands of genes in thousands of cells at the same time at different time points along the way, and determine which gene expression programs were silenced - and which were active in each cell and in each colony.

epigenetic memory

"To our surprise," says Meir, "we discovered a significant component of epigenetic memory in the cancer cells. The daughter cells inherited the epigenetic mechanisms of the mother cells almost as if it were their genetic identity. In fact, we had to go back and make sure that it was indeed not their genetic identity."

In some of the cells, which originated from the colon cancer tumor, the researchers examined the epigenetic composition in the prostate, by examining one of the most important epigenetic mechanisms - DNA methylation; A biochemical process during which a methyl group is attached to a genetic segment, thereby determining the level of transcription of a particular gene. Their findings showed that as the generations passed, some of the methyl groups dropped or moved, and these epigenetic changes accumulated faster than the rate of genetic mutations. "Even when not many mutations were recorded over the generations, the methylation continued to loosen slowly, and became less and less reliable," says Prof. Tanay. "This slow deterioration of the epigenetic memory may help accelerate cancer progression, as it means a gradual loss of control over gene expression."

The researchers also discovered that in some cells the loss of epigenetic memory helped them gradually forget what type of cell they were meant to be, and thus they could transform into other cell types and migrate to new areas of the body - or in other words: become cancerous metastases. "The progression of cancer is affected by genetic mutations, but in between there are also gradual changes in epigenetics that may push the cells in a more cancerous direction," says Prof. Tanay.