Rai Kodan wrote the book that won the award with the help of artificial intelligence that gave her complete sentences - which the author inserted in the book in its entirety. She estimated that about five percent of the entire text in the book consisted of sentences that she copied directly from the ChatGPT artificial intelligence engine

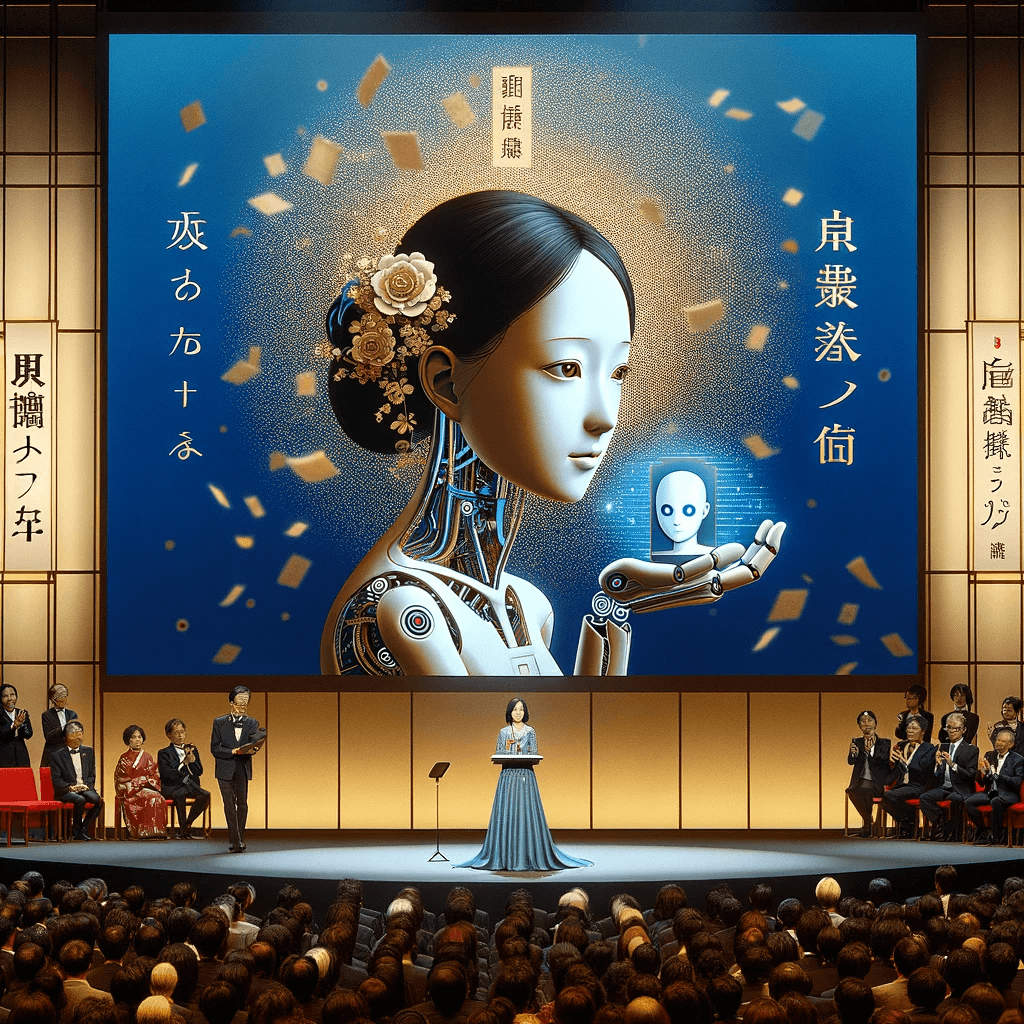

Rai Kodan took the stage to receive the Akutagawa Prize: one of the most prestigious literary awards in Japan. The book was a success among the general public, and the judging committee also called it "without any flaw".

Then Kodan admitted that she wrote it with the help of artificial intelligence. Not only did the artificial intelligence give her ideas, but also complete sentences - which the author inserted in the book in full. She estimated that about five percent of the entire text in the book consisted of sentences that she copied directly from the ChatGPT artificial intelligence engine.

And the internet, of course, exploded.

Kodan was criticized by Ruthin for the use of artificial intelligence in her work, for the fact that she "disgraces" the writers who choose to write without technological aids, and for every choice she made in her life until the moment her name reached Twitter. She, for her part, clarified with a calm smile at the award ceremony that she "intends to continue to profit from the use of artificial intelligence in writing my books, while I let my creativity fully express itself."

Welcome to the new generation of writers: those who use artificial intelligence to upgrade their abilities, and have no intention of apologizing for it.

And these multiply quickly.

About writers and understanding

Writing workshops have always been a common thing, but lately they seem to have picked up steam, especially in one particular subfield: AI-assisted writing. The instructors teach the students – who range in age from 16 to 70 – how to use artificial intelligence tools like the famous ChatGPT to do, well, everything. The writers learn to use artificial intelligence to get ideas for stories that have not yet been written, to receive constructive criticism on drafts they have already written, to enrich, deepen and add life to their descriptions, to proofread and provide linguistic advice. In short, they provide the full range of services that a human editor would provide to writers. But suddenly, any writer - no matter how poor or poor - can benefit from such a close editor throughout the writing process, from beginning to end, at zero cost.

The entrepreneurs have already noticed the need that writers have, and are trying to provide them with an answer with artificial intelligences that are better adapted to the craft. Squibler, for example, helps writers "shape detailed narratives, and is particularly successful in its scene description capabilities. This allows writers to effortlessly create environments that draw the reader into the content, making the stories feel more real and alive.” Neuroflash helps writers create detailed character profiles, generate dialogue between characters, or even whole paragraphs and pages of text. Writesonic offers help in twisting the plot, describing the characters and changing the writer's writing style to let him experiment with new and different ways to convey the message.

The costs, as I already said, are ridiculous. They range from temporary use of the platform for free, to a subscription for 'heavy' writers that can reach forty dollars or so in the more expensive apps. This means that at a cost of five shekels per day, anyone can today enjoy writing skills that human writers labored for decades to acquire with blood, sweat and a lot of banging of the head on the keyboard.

So what's the wonder that writers use all this abundance?

who uses

Jennifer Lapp is considered a successful writer - that is, one who is able to write books as a way to make a living. All she has to do is publish a new book every nine weeks. The amazing thing is that she kept up with this pace even before she started using artificial intelligence. In the last year, she discovered the artificial intelligence engines and began to work them at a brisk pace so that they would complete paragraphs and even entire scenes for her. She fed the artificial intelligence the synopsis of the requested scene, went through the results and modified as needed. Her productivity increased by 23.1 percent - she counts by words, because at this hectic pace she has no other choice.

Of course, readers immediately noticed that her style had changed.

Sorry, that was a joke.

In fact, readers found no hint that anyone had written the new texts for her. They didn't realize that something had changed. Lep was even a little offended when she found out that some of the sentences that the readers marked as particularly successful, came from the machine. Even her husband He couldn't find the difference between the sentences produced by the artificial intelligence and those written by the brain between the walls of his wife's skull.

Lep is far from alone in the race for fast, quality and profitable writing. Last year, a Chinese professor managed to write a short science fiction book in only three hours, submitted it to a national competition - and won second place. Another science fiction writer, Tim Boucher, wrote 97 short science fiction books in nine months. The length of each book reaches 2,000 to 5,000 words, and Boucher added and used artificial intelligence to enrich them with illustrations. He plans to reach at least a thousand books, if not more.

These are just a few of the great success stories, but it is likely that there are thousands more writers who have already started using artificial intelligence to support the writing and creative process. Not everyone admits it, but looking from the side it is clear that something is changing. If only because Amazon recently decided to limit the publishing rate of authors to three new books a day. The flood of book publishing left her no other choice.

But are these books really 'worthy'? Are they successful? are they good

Let's face it: probably not. Artificial intelligence has not yet reached a level of writing that allows it to produce complete books that have order and internal logic. At best, she is able to produce episodes or short stories - and even these probably won't win prizes in competitions... yet. In the meantime, we still need the human writers to take the products of the artificial intelligence, sand them, sharpen them, edit and delete and disassemble and put them together and sometimes also throw them in the trash and write a new story based on the ideas that it sparked in them during all this work.

And despite all that, the direction the wind is blowing is already clear to the community of writers. The profession is in danger - and the writers are called to the flag.

pride and Prejudice

Many of today's established authors are suspicious of artificial intelligence for a very prosaic and business-like reason: they believe that it learned from them without giving it explicit permission to do so. They are probably right too. OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, Claimed in mid-2023 For allegedly training her artificial intelligence on pirated books. Another claim from the end of 2023 Coordinates 17 well-known writers - John Grisham and George R.R. Martin are just two of them - demanding to prevent "The extinction of the writer's profession", as they describe it. At the same time, more than 10,000 writers—including people like Margaret Atwood and James Patterson—signed open letter which requires OpenAI to obtain clear permission from authors to train the artificial intelligence on their works, and to provide them with a fair reward for doing so.

This situation, in which the entire international writers' guild is bending over backwards and going to war with artificial intelligence, certainly does not make it easier for writers to use it or evaluate it in a more balanced way. It's no exaggeration to say that there is a lot of bad feeling right now directed towards artificial intelligence. as written by one -

"The mere thought of being caught using ChatGPT will make some writers nauseous. Words like "cheat" may be thrown their way if such a thing is discovered. In the end, there is probably no way to restore that kind of reputational damage."

These are all understandable and even expected reactions to such a new and powerful technology. It should be mentioned that ChatGPT was released to the public only a year and a half ago. It's not even a flicker of the candle flame in historical terms. We also know that every new and game-changing technology met with similar resistance - and hysterical no less - from those who were expected to lose their livelihood and their hard-earned reputation because of it. The monks whose main job was copying books, strongly opposed Gutenberg's printing press which replaced them almost overnight. The portrait painters look at the camera. Animators were creeped out by the idea that cartoons would be produced using computer graphics, rather than painstakingly drawing frame-by-frame by hand. "Where's the feeling?" they all asked. "Where is the human depth that my work gives to the final piece?"

And yet - move move move. When technology reached a state advanced enough to replace the human craftsman in his work, it did so. Today, hand-copied books are only found in very specific and limited sectors. The vast majority of books are printed by machines. A vast majority of the portraits in school yearbooks were produced using a camera. Cartoons today almost always involve very little manual work. And despite all these developments - we enjoy the books, the portraits and the films no less than our ancestors from six hundred years ago, two hundred years and thirty years ago. History repeats itself.

And there is at least one type of writer who already understands this well.

The Great Screenwriters Rebellion

In the middle of 2023, the Screenwriters Guild of America started a strike that was seen by many as a kind of attempt to fight windmills. There were several reasons for the strike, but the most important of them was the breakthrough of artificial intelligence into the arena of history - and the immediate realization of the screenwriters that there was a technology that directly threatened their livelihood.

Usually when new technologies mature, it takes time for people to realize that they are going to threaten their profession. But the rate of progress today is so fast, that screenwriters woke up overnight and found themselves in a world where artificial intelligence engines can reduce the work time of writers by dozens of percent. Worse, it can enable everyone to do their job at a reasonable level.

The concern of the screenwriters is not from science fiction scripts (sorry). The screenwriters team focused on situations that it already recognizes today that are starting to happen: that an artificial intelligence will write a bad-to-mediocre script, and a Hollywood screenwriter will be hired to improve it for minimum hourly wages, for example. In this case, the human screenwriter loses an important source of income - the writing of the script from the beginning - and the credits that were supposed to be in his name.

Screenwriters are already starting to use AI today to write paragraphs of colorful descriptions, find names for restaurants in foreign languages, generate parts of dialogue between characters and much more. It turns out that the artificial intelligence significantly reduces the time required for the human screenwriter to write the script. And since some screenwriters are paid by the hour, here they lose half of their working hours - and half of their income.

But if this is the case, how does the strike help them?

Well, contrary to all her expectations, the screenwriters' strike actually led for excellent results for them, given the situation. The Screenwriters Guild has reached an agreement with the producers that they will not be allowed to require the screenwriters to use artificial intelligence, or to give them scripts produced by artificial intelligence without informing them about it. the screenwriters Yes can choose to use artificial intelligence to do their jobs faster and better, as long as the products meet the standards expected of them.

What does the agreement that the screenwriters signed teach us? First of all, that they are practical: they understand that they cannot fight game-changing technology like artificial intelligence, so they find the middle ground. They allow the use of technology to produce scripts, and at the same time demand that they be remunerated as before for their services - even if they use it.

Will this agreement survive for long? Pretty obviously not. It is only valid for three years, and the closer we get to 2030, the more the capabilities of artificial intelligence will increase. There are estimates that by 2027 we will already have developed general artificial intelligence, which will be able to produce complete scripts at a high level. And if not until 2027, then a year later. or two years. or five. As mentioned, the trend is clear and the end is known in advance. A gun lying on the table in the first act, etc.

The screenwriters are not suckers. They understand it, at least tacitly and implicitly. They know that they should already start finding a new profession - or transform their profession themselves. how? With artificial intelligence, of course. And so the agreement allows them to use artificial intelligence themselves and acquire skill in this new and powerful tool, in the hope that they will find the new way forward.

They better hurry. Once artificial intelligence can write complete scripts well (and by implication, books as well), you can count on the companies to kick the annoying human screenwriters to hell, and buy a subscription to produce scripts in motion picture at a ridiculous cost.

And that would be wonderful.

A world of creation

Six months ago I gave a lecture at an embassy event in the world about artificial intelligence, and how anyone could use it to write books, one day. At the end of the lecture, one of the guests approached me - a large American - and poured his heart out to me. He belonged to the team of screenwriters, and said with real pain that artificial intelligence is about to take the place of human screenwriters, and the world will lose the beautiful, perfect and meticulous writing that characterizes television series today. According to him, at least.

I suspect the truth is very different. What will happen in reality will be more similar to the revolution that platforms for creators have brought to our lives: YouTube, Tiktok, Roblox and others. These platforms put the tools in the hands of every child to create videos, talk shows and even computer games. Have piles of garbage been created? for sure. This happens in any situation where the work is open to everyone. And at the same time, ordinary people could express themselves in ways that in the past required an investment of tens of thousands of dollars - for writing, editing and photography teams, renting a studio with cameras, and more - to implement. The world opens up for the new creators.

This is what will also happen in the field of screenwriting and writing in the next decade, thanks to artificial intelligence. This is what we are starting to see already, when the machine does a significant part of the writing - and the human is only the navigator and manager of the larger process.

What will such a writing process look like in the next decade?

Each according to his ability, each according to the needs of the process

Several years ago I outlined a series of strategic proposals for a particular organization. I clarified that these are only suggestions, and that the managers in the organization should now consider them carefully and provide feedback regarding the way forward. The CEO was impressed by the proposals, and invited me to the board meeting to see how he shares these initial ideas with the VPs and receives feedback from them.

It wasn't pretty.

For almost an hour, the cautious suggestions that I formulated as the beginning of a complex thought process, were placed on the heads of the VPs like a five-kilo hammer, as tactical orders that cannot be resisted. He shot them off quickly, while his subordinates struggled to write and remember everything. When asked to make a comment, he quickly ignored or skipped over it. "Leave the small details!" barked "Just do it!"

He finished the show, got up, announced that the session was over and left the room. One of the junior managers patted me sympathetically on the back as they all dispersed. He probably knew the look on my face.

"It's okay," he whispered to me. "The man is a fighter pilot."

A little consultation with my friends from the Air Force revealed that this is indeed a useful stereotype. A fighter pilot, it was explained to me, does not deal with ambiguity. He owes unequivocal and clear answers. His training taught him to react quickly and decisively, with a self-confidence second to none. And as one of my friends concluded with a roll of the eyes: the dominant male. Only the navigators and helicopter pilots approach their place in the flock. The rest of the human beings are far below, except for the accountants and income tax officials. I will get to them later in the article. Don't worry - we will include everyone.

The fighter pilot is only part of a complex process that requires people from all professions and all types of personality. He may be the best person to keep the plane in real time while in the air and under fire, but he couldn't have gotten to this point without a few dozen OCD aircraft technicians making sure every part of the plane is ready for action. He would not have been able to find the right target without the involvement of the cautious and cautious intelligence officers, who consider several ways to attack and formulate the most appropriate tactic. And he wouldn't have been able to figure out what to do without the pit control people explaining to him - slowly and with consideration for his dignity, then quickly and shouting - how he should act immediately after he leaves the aerial battle.

We have gotten used to the fact that writers are the 'fighter pilots': they are the ones at the center of the process, and everything revolves around them. The editors, the publishers, the publicists - they all serve the writers, because they do the extraordinary part of the work, which they are only rarely able to execute at a high level.

Now artificial intelligence will be able to perform part of the writing process, and as a result, successful writers will no longer be as rare as they were in the past. The process will reorganize itself in a flatter way, where people of all kinds can carry out the process of writing, editing, publishing and so on. Artificial intelligence will, of course, play a part at every stage - and especially in writing. The authors will lose a large part of their prestige, but we can all enjoy a huge wealth of books. In the end, everyone – except the most elite writers – will benefit from this progress.

But what about the magic of writing?!

Edgar Allan Poe is known as one of the greatest poets of the 19th century. His works, such as "The Raven" and "Annabelle Lee", evoke melancholy and grief in the reader. Or in other words, connecting the reader to the human experience and the very human concepts of death, loss and bereavement. The words flow and rhyme with each other, and the heart beats together with them.

When we read Poe's "The Raven", it's hard not to connect to the writing theory of another great poet: Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who argued that the craft of writing cannot be broken down into its separate parts. Great poems, according to Coleridge, are the product of 'human spontaneity', of the human imagination that opposes the order and logic that characterize the cold "machines" and the income tax officials and accountants.

Well, now I managed to insult everyone?

Coleridge's theory may have been valid for him - perhaps - but in 1846 Poe decided to make a shocking confession. he wrote Article for the general public, in which he completely dismissed the idea that artists create poems - or books - out of thin air, in a fit of divine inspiration. Instead, he made it clear that the writing process is methodical and careful, and that most writers prefer not to allow the public to peek behind the scenes of the writing process, so that innocent human beings do not lose their sense of holiness.

All this happened on the first page of the article, where he managed to arouse the anger of most of the poets of those days. One can only imagine the reaction of those poets when they turned the page and discovered that Poe details his writing process later in the article, and even clarifies how he wrote "The Crow", step-by-step. I would not be surprised to find out that the same steps will be taken in a few years for advanced artificial intelligence, for it will produce a series of poems that rival those of Poe.

The writing process, dear readers, is not magical. Put bluntly, it's garbage of a process. Very few of the works produced are perfect on the first attempt. The writers and poets produce draft after draft, change and sand and refine and carve the work, and sometimes also throw it in the trash in frustration and rewrite it. In every draft and every stage of editing, they try to understand how to improve the work according to quantitative measures - even if they express themselves with the statement "I like this better".

We readers are only exposed to the finished work at the end of this excruciating process. Sometimes it is better, sometimes less. But let's not forget: the process exists behind almost every literary work.

Artificial intelligence will, at least in the next decade, do a great thing: it will make it easier for writers and poets to move forward in this process. It will lower the level of difficulty and challenges in the process, and allow anyone to produce the works. Yes, not only for the tortured poets sitting at their desks at three in the morning with only the light of the candle hosting them for company. Even children will be able to write great poems.

or not. Because now - and here I will reach the end point - we need to understand: what makes a work "great"?

What makes a work "great"?

The real magic

Is it the rhyme that makes "the crow" an immortal work? But rhyming is just a game of combinatorics and crossing words. Rhyme can make a work "good", but not "great".

Maybe it's about the length of a piece? The famous author Marcel Proust would surely agree with this statement, as the one who wrote the longest literary work In the world, with over a million words. But according to the same principle, book series - and even the multitude of scripts for the Simpsons television series, which has been around for more than thirty years - are "great" works. And maybe they really are, but this answer will certainly not please the writers who feverishly search for the uniqueness of human creation.

The answer, in my opinion, is that many works can be "good", but only man-made works can be "great".

The reason is that the greatness of a human creation is expressed in the fact that it is groundbreaking in relation to the circumstances in which it was created. A great work is not one that only a few can create, but only a few dare create a. The greatest poets of their generation are those who opposed the existing norms of writing, and produced a work of poetry that captured the public's attention with its innovation and subversion - and was also written well enough to justify its reading. We appreciate not only the work itself, but also the extraordinary creator and his willingness to take risks, to expose himself, to bravely confront the barrage of rotten tomatoes and rotten eggs.

And so, here are two predictions to conclude.

First, in the coming years we will be exposed to a huge collection of "good" works. Every sharp-nosed child will write good books, and a few years later, it will be the artificial intelligence itself that will write the good books. We will enjoy reading these books and watching the TV shows that the computer screenwriters will produce. We will enjoy a world of enormous wealth of content in the various mediums: books, podcasts, television and everything else.

Secondly, these works may be good, but most of them are not called "greatness", and certainly it is not claimed that the artificial intelligence behind them is endowed with any "greatness". Simply because they will not be groundbreaking, and no one will risk the process of writing these works.

Which works will be "great"? Those who are real people will take risks in their writing and publication. Maybe those humans will use artificial intelligence as a tool. They might even use it to write most of the piece. But in the end, the person who will put his name on this work, is the one who will risk and put himself in the center. And if it is indeed innovative, groundbreaking and extraordinary - then he will be rewarded by being defined as "great" and he will become a great creator in the eyes of the public and in the eyes of history.

When Rai Kodan stood in front of all of Japan and announced that she had used artificial intelligence to write her book, she was truly daring. She was willing to risk and die for her art. She put herself and her reputation on the line to make an important argument: that it is possible and correct to use artificial intelligence as part of the writing process. She knew that some writers would be attacked "nauseum", and that "there is probably no way to restore this kind of reputational damage," according to the critics.

And she looked at the camera, smiled, and said that she would continue to write books in this way.

And thus, truly, she became a great writer.