A management researcher from the University of Essex argues that true discovery and progress cannot rely on the minds and motivations of a few famous men. This involves investing in institutions that are anchored in democracy and sustainability - not only because it is more ethical, but because in the long run, it will be much more effective

By: Peter Bloom, Professor of Management, University of Essex

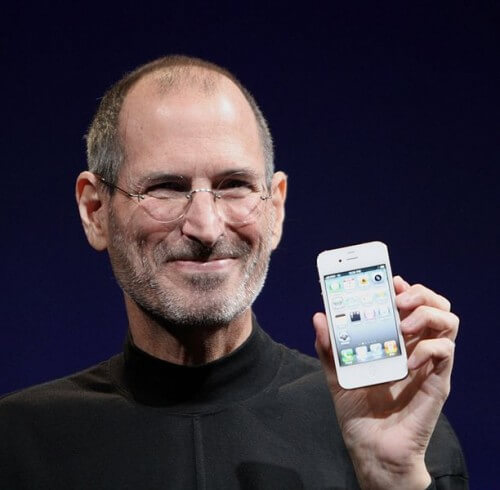

Technological innovation in recent decades has brought great fame and wealth to high-tech giants such as Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos. Often referred to as geniuses, they are the face behind the gadgets and media that so many of us depend on.

Sometimes they are controversial. Sometimes their level of influence is controlled.

But they also enjoy a common myth that elevates their status. The same myth is the belief that "visionary" CEOs at the head of huge corporations are the engines that drive vital breakthroughs that public organizations are too lazy or too futuristic to make.

There are many who believe that the private sector is much better equipped to solve major challenges than the public sector. We see such ideology embodied in ventures like OpenAI. This successful company was founded on the premise that while artificial intelligence is too important to be left to corporations alone, the public sector simply cannot keep up.

The approach is related to a political philosophy that favors the idea of pioneering entrepreneurs as role models who advance civilization through genius and personal determination.

In reality, however, most modern technological components – such as car batteries, space rockets, the Internet, smart phones and GPS – grew out of publicly funded research. They were not the product of the inspired work of the masters of the corporate universe.

And my work points to another disconnect: that the apparent profit motive in Silicon Valley (and beyond) often inhibits innovation rather than promotes it.

For example, attempts to profit from the corona vaccine have negatively affected the global accessibility of the drug. Or consider how recent tourism trips to space seem to focus on creating experiences for the wealthiest people over less profitable but more scientifically valuable missions.

More generally, the thirst for profit means that restrictions on intellectual property tend to limit cooperation between (and even within) companies. There is also evidence that short-term shareholder demands distort genuine innovation in favor of financial rewards.

Allowing profit-oriented executives to set the technology agenda can also entail public costs. It is expensive to deal with low-Earth orbit debris caused by space tourism, or complex regulatory negotiations involved in protecting human rights around artificial intelligence.

Therefore there is a clear tension between profit requirements and long-term technological progress. And this partly explains why major historical innovations have emerged from public sector institutions that are relatively insulated from short-term financial pressures. Market forces alone rarely achieve game-changing breakthroughs like the space programs or the creation of the Internet.

Excessive corporate control has further diluting effects. Research scientists seem to spend valuable time chasing funding influenced by business interests. They are also increasingly incentivized to go into the lucrative private sector.

Here the talents and abilities of those scientists and engineers may be directed to help advertisers better hold our attention. Or they may be required to find ways in which companies can make more money from our personal data.

Projects that can address climate change, public health or global inequality are less likely to be in focus.

It also seems that university laboratories are moving to a "science for profit" model through partnerships with industry.

Digital destiny But true scientific innovation requires institutions and people guided by principles that go beyond financial incentives. And luckily, there are places that support them.

"Open knowledge institutions" and platform cooperatives are focused on innovation for the common good and not personal glory. Governments can do much more to support and invest in these types of organizations.

If they do, the coming decades may see the development of healthier innovation systems that go beyond corporations and the control of CEOs. They will create an environment of cooperation rather than competition, for real social good.

There will still be room for the "genius" eccentricity of Musk and Zuckerberg and their fellow Silicon Valley billionaires. But relying on their bloated corporations to shape and control technological innovation is a mistake.

Because true discovery and progress cannot rely on the minds and motives of a few famous men. This involves investing in institutions that are anchored in democracy and sustainability - not only because it is more ethical, but because in the long run, it will be much more effective.

For an article in The Conversation

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- False prophets: how Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk are misleading the digital economy

- Elon Musk disrupted a Ukrainian autonomous submarine attack on the Russian navy; It was feared that it would lead to a nuclear war

- Sam Altman CEO of OPEN AI: We need to build a control mechanism for artificial intelligence like the Atomic Arms Control Council (video)

One response

Obviously. We need to take the power out of the hands of the "white European man" (even though most of these technology entrepreneurs are crazy leftists anyway) and give it to the residents of American universities, who are crazy about white hatred and reverse racism (with the excuse that "it's not racism"), anti-Semitism, misandry, hatred of science and religion ( unless it is Islam - the religion of peace and love), the hatred of "hetero-normativity" (as they call it) and everything that smells of Western culture.